A Practical Guide to Running Postgres on Kubernetes

Deploy, scale, and secure Postgres on Kubernetes. Our technical guide covers operators, storage, HA, security, and monitoring for cloud-native databases.

Running Postgres on Kubernetes means deploying and managing your PostgreSQL database cluster within a Kubernetes-native control plane. This approach transforms a traditionally static, stateful database into a dynamic, resilient component of a modern cloud-native architecture. You are effectively integrating the world's most advanced open-source relational database with the industry-standard container orchestration platform.

The Case for Postgres on Kubernetes

Historically, running stateful applications like databases on Kubernetes was considered an anti-pattern. Kubernetes was designed for stateless services—ephemeral workloads that could be created, destroyed, and replaced without impacting application state. Databases, requiring stable network identities and persistent storage, seemed antithetical to this model.

So, why has this combination become a standard for modern infrastructure?

The paradigm shifted as Kubernetes evolved. Core features were developed specifically for stateful workloads, enabling engineering teams to consolidate their entire operational model. Instead of managing stateless applications on Kubernetes and databases on separate VMs or managed services (DBaaS), everything can now be managed declaratively on a single, consistent platform.

This unified approach delivers significant technical and operational advantages:

- Infrastructure Portability: Your entire application stack, database included, becomes a single, portable artifact. You can deploy it consistently across any conformant Kubernetes cluster—public cloud, private data center, or edge locations—without modification.

- Workload Consolidation: Co-locating database instances alongside your applications on the same cluster improves resource utilization and efficiency. It reduces infrastructure costs by eliminating dedicated, often underutilized, database servers.

- Unified Operations: Your team can leverage a single set of tools and workflows (

kubectl, GitOps, CI/CD pipelines) for the entire stack. This simplifies operations, streamlines automation, and reduces the cognitive load of context-switching between disparate systems.

A Modern Approach to Data Management

A key driver for moving databases to Kubernetes is the ability to achieve a single source of truth for your data, which is fundamental for data consistency and reliability. With Kubernetes adoption becoming ubiquitous, it is the de facto standard for container orchestration. By 2025, over 60% of enterprises have adopted it, with some surveys showing adoption as high as 96%. You can explore this data further and learn more about Kubernetes statistics.

By treating your database as a declarative component, you empower the Kubernetes control plane to manage its lifecycle. Kubernetes handles complex operations—automated provisioning, self-healing from node failures, and scaling—transforming what were once manual, error-prone DBA tasks into a reliable, automated workflow.

Ultimately, running Postgres on Kubernetes is not merely about containerizing a database. It's about adopting a true cloud-native operational model for your data layer. This unlocks the automation, resilience, and operational efficiency required to build and maintain modern, scalable applications. The following sections provide a technical deep dive into how to implement this.

Choosing Your Postgres Deployment Architecture

When deploying Postgres on Kubernetes, the first critical decision is the deployment methodology. This architectural choice fundamentally shapes your operational model, dictating the balance between granular control and automated management. The two primary paths are a manual implementation using a StatefulSet or leveraging a dedicated Kubernetes Operator.

The optimal choice depends on your team's Kubernetes expertise, your application's Service Level Objectives (SLOs), and the degree of operational complexity you are prepared to manage.

This decision tree frames the initial architectural choice.

As the chart indicates, the primary drivers for this architecture are the requirements for a database that can scale dynamically and be deployed portably—core capabilities offered by running Postgres on Kubernetes.

The Manual Route: StatefulSets

A StatefulSet is a native Kubernetes API object designed for stateful applications. It provides foundational guarantees, such as stable, predictable network identifiers (e.g., postgres-0.service-name, postgres-1.service-name) and persistent storage volumes that remain bound to specific pod identities. When you choose this path, you are responsible for building all database management logic from the ground up using fundamental Kubernetes primitives.

This approach offers maximum control. You define every component: the container image, storage provisioning, initialization scripts, and network configuration. For teams with deep Kubernetes and database administration expertise, this allows for a highly customized solution tailored to specific, non-standard requirements.

However, this control comes with significant operational overhead. A basic StatefulSet only manages pod lifecycle; it has no intrinsic knowledge of PostgreSQL's internal state.

- Manual Failover: If the primary database pod fails, Kubernetes will restart it. However, it will not automatically promote a replica to become the new primary. This critical failover logic must be scripted, tested, and managed entirely by your team.

- Complex Upgrades: A major version upgrade (e.g., from Postgres 15 to 16) is a complex, multi-step manual procedure involving potential downtime and significant risk of data inconsistency if not executed perfectly.

- Backup and Restore: You are solely responsible for implementing, testing, and verifying a robust backup and recovery strategy. This is a non-trivial engineering task in a distributed system.

The Automated Path: Kubernetes Operators

A Kubernetes Operator is a custom controller that extends the Kubernetes API to manage complex applications. It acts as an automated, domain-specific site reliability engineer (SRE) that lives inside your cluster.

An Operator encodes expert operational knowledge into software. It automates the entire lifecycle of a Postgres cluster, from initial deployment and configuration to complex day-2 operations like high availability, backups, and version upgrades.

Instead of manipulating low-level resources like Pods and PersistentVolumeClaims, you interact with a high-level Custom Resource Definition (CRD), such as a PostgresCluster object. You declaratively specify the desired state—"I require a three-node cluster running Postgres 16 with continuous archiving to S3"—and the Operator's reconciliation loop works continuously to achieve and maintain that state. This declarative model simplifies management and minimizes human error.

The Operator pattern is the primary catalyst that has made running stateful workloads like Postgres on Kubernetes a mainstream, production-ready practice. A leading example is EDB's CloudNativePG, a CNCF Sandbox project. It manages failover, scaling, and the entire database lifecycle through a simple, declarative API, abstracting away the complexities of manual management.

Comparing Deployment Methods: StatefulSet vs Operator

To make an informed architectural decision, it's crucial to compare these two methods directly. The table below outlines the key differences.

| Feature | Manual StatefulSet | Kubernetes Operator |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Deployment | High complexity; requires deep Kubernetes & Postgres knowledge. | Low complexity; a declarative YAML file defines the entire cluster. |

| High Availability | Entirely manual; you must build and maintain all the failover logic yourself. | Automated; handles leader election and promotes replicas for you. |

| Backups & Recovery | Requires custom scripting and integrating external tools. | Built-in, declarative policies for scheduled backups & Point-in-Time Recovery (PITR). |

| Upgrades | Complex, high-risk manual process for major versions. | Automated, managed process with configurable strategies to minimize downtime. |

| Scaling | Manual process of adjusting replica counts and storage. | Often automated through simple updates to the custom resource. To learn more, check out our guide on autoscaling in Kubernetes. |

| Operational Overhead | Very High; your team is on the hook for every single "day-2" task. | Low; the Operator takes care of most routine and complex tasks automatically. |

| Best For | Learning environments or unique edge cases where you need extreme, low-level customization. | Production workloads, large database fleets, and any team that wants to focus on building features, not managing infrastructure. |

This comparison makes the trade-offs clear. While the manual StatefulSet approach offers ultimate control, the Operator path provides the automation, reliability, and reduced operational burden required for most production systems.

Mastering Storage and Data Persistence

The fundamental requirement for any database is the ability to reliably persist data. When you run Postgres on Kubernetes, you are placing a stateful workload into an ecosystem designed for stateless, ephemeral containers. A robust storage strategy is therefore non-negotiable.

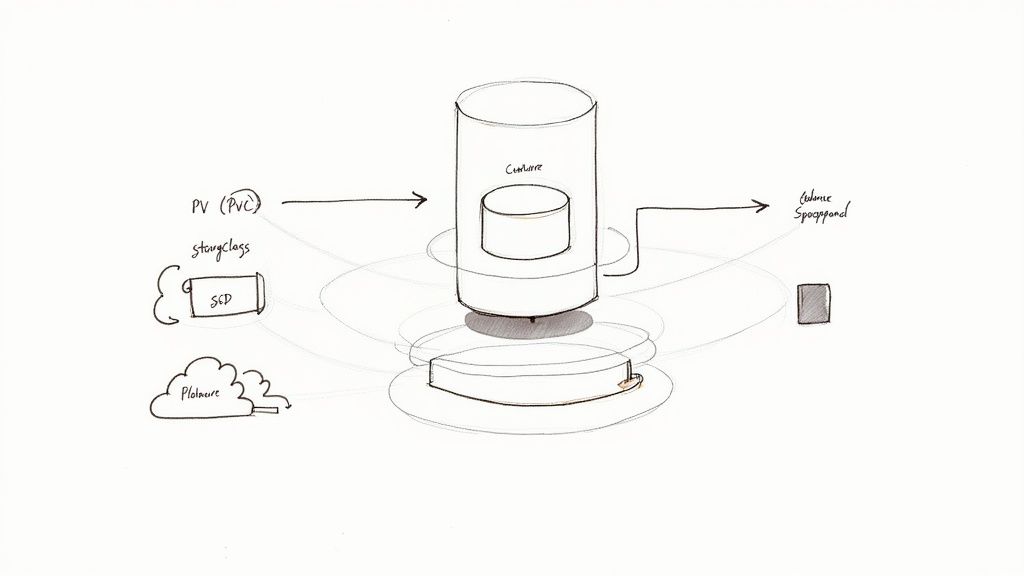

The primary goal is to decouple the data's lifecycle from the pod's lifecycle. Kubernetes provides a powerful abstraction layer for this through three core API objects: PersistentVolumes (PVs), PersistentVolumeClaims (PVCs), and StorageClasses.

Think of a Pod as an ephemeral compute resource. When it is terminated, its local filesystem is destroyed. The data, however, must persist. This is achieved by mounting an external, persistent storage volume into the pod's filesystem, typically at the PGDATA directory location.

Understanding Core Storage Concepts

A PersistentVolume (PV) is a piece of storage in the cluster that has been provisioned by an administrator or dynamically provisioned using a StorageClass. It is a cluster resource, just like a CPU or memory, that represents a physical storage medium like a cloud provider's block storage volume (e.g., AWS EBS, GCE Persistent Disk) or an on-premises NFS share.

A PersistentVolumeClaim (PVC) is a request for storage by a user or application. It is analogous to a Pod requesting CPU and memory; a PVC requests a specific size and access mode from a PV. Your Postgres pod's manifest will include a PVC to claim a durable volume for its data directory.

This separation of concerns between PVs and PVCs is a key design principle. It allows application developers to request storage resources without needing to know the underlying infrastructure details.

The most critical component enabling full automation is the StorageClass. A StorageClass provides a way for administrators to describe the "classes" of storage they offer. Different classes might map to different quality-of-service levels, backup policies, or arbitrary policies determined by the cluster administrator. When a PVC requests a specific

storageClassName, Kubernetes uses the corresponding provisioner to dynamically create a matching PV.

Choosing the Right StorageClass

The storageClassName field in your PVC manifest is one of the most impactful configuration decisions you will make. It directly determines the performance, resilience, and cost of your database's storage backend.

Key considerations when selecting or defining a StorageClass:

- Performance Profile: For a high-transaction OLTP database, select a StorageClass backed by high-IOPS SSD storage. For development, staging, or analytical workloads, a more cost-effective standard disk tier may be sufficient.

- Dynamic Provisioning: This is a mandatory requirement for any serious deployment. Your StorageClass must be configured with a provisioner that can create volumes on-demand. Manual PV provisioning is not scalable and defeats the purpose of a cloud-native architecture.

- Volume Expansion: Your data volume will inevitably grow. Ensure your chosen StorageClass and its underlying CSI (Container Storage Interface) driver support online volume expansion (

allowVolumeExpansion: true). This allows you to increase disk capacity without database downtime. - Data Locality: For optimal performance, use a storage provisioner that is topology-aware. This ensures that the physical storage is provisioned in the same availability zone (or locality) as the node where your Postgres pod is scheduled, minimizing network latency for I/O operations.

Below is a typical PVC manifest. It requests 10Gi of storage from the fast-ssd StorageClass.

apiVersion: v1

kind: PersistentVolumeClaim

metadata:

name: postgres-pvc

spec:

storageClassName: fast-ssd

accessModes:

- ReadWriteOnce

resources:

requests:

storage: 10Gi

Understanding Access Modes

The accessModes field is a critical safety mechanism. For a standard single-primary PostgreSQL instance, ReadWriteOnce (RWO) is the only safe and valid option.

RWO ensures that the volume can be mounted as read-write by only a single node at a time. This prevents a catastrophic "split-brain" scenario where two different Postgres pods on different nodes attempt to write to the same data files simultaneously, which would lead to immediate and unrecoverable data corruption.

While other modes like ReadWriteMany (RWX) exist, they are designed for distributed file systems (like NFS) and are not suitable for the data directory of a block-based transactional database like PostgreSQL. Always use RWO.

Implementing High Availability and Disaster Recovery

For any production database, ensuring high availability (HA) to withstand localized failures and disaster recovery (DR) to survive large-scale outages is paramount. When running Postgres on Kubernetes, you can architect a highly resilient system by combining PostgreSQL's native replication capabilities with Kubernetes' self-healing infrastructure.

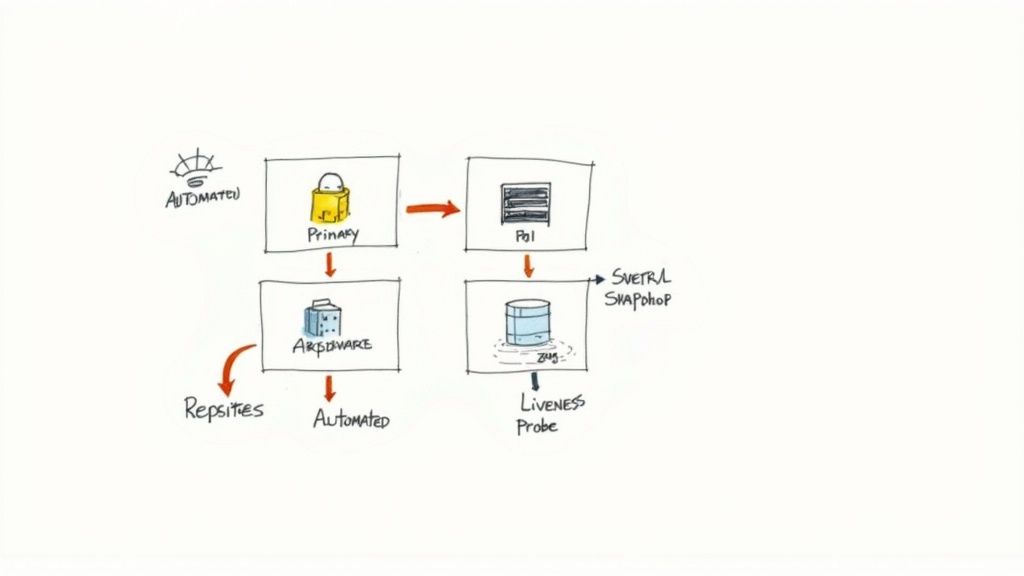

The core of Postgres HA is the primary-replica architecture. A single primary node handles all write operations, while one or more read-only replicas maintain a synchronized copy of the data. The key to HA is the ability to detect a primary failure and automatically promote a replica to become the new primary with minimal downtime. A well-designed Kubernetes Operator excels at orchestrating this process.

Building a Resilient Primary-Replica Architecture

PostgreSQL's native streaming replication is the foundation for this architecture. It functions by streaming Write-Ahead Log (WAL) records from the primary to its replicas in near real-time. There are two primary modes of replication, each with distinct trade-offs.

Asynchronous Replication: This is the default and most common mode. The primary commits a transaction as soon as the WAL record is written to its local disk, without waiting for acknowledgment from any replicas.

- Pro: Delivers the highest performance and lowest write latency.

- Con: Introduces a small window for potential data loss. If the primary fails before a committed transaction's WAL record is transmitted to a replica, that transaction will be lost (Recovery Point Objective > 0).

Synchronous Replication: In this mode, the primary waits for at least one replica to confirm that it has received and durably written the WAL record before reporting a successful commit to the client.

- Pro: Guarantees zero data loss (RPO=0) for successfully committed transactions.

- Con: Increases write latency, as each transaction now incurs a network round-trip to a replica.

The choice between asynchronous and synchronous replication is a critical business decision, balancing performance requirements against data loss tolerance. Financial systems typically require synchronous replication, whereas for many other applications, the performance benefits of asynchronous replication outweigh the minimal risk of data loss.

The Kubernetes Role in Automated Failover

While Kubernetes is not inherently aware of database roles, it provides the necessary primitives for an Operator to build a robust automated failover system.

The objective of automated failover is to detect primary failure, elect a new leader from the available replicas, promote it to primary, and seamlessly reroute all database traffic—all within seconds, without human intervention.

Several Kubernetes features are orchestrated to achieve this:

- Liveness Probes: Kubernetes uses probes to determine pod health. An intelligent Operator configures a liveness probe that performs a deep check on the database's role. If a primary pod fails its health check, Kubernetes will terminate and restart it, triggering the failover process.

- Leader Election: This is the core of the failover mechanism. Operators typically implement a leader election algorithm using Kubernetes primitives like a

ConfigMapor aLeaseobject as a distributed lock. Only the pod holding the lock can assume the primary role. If the primary fails, replicas will contend to acquire the lock. - Pod Anti-Affinity: This is a non-negotiable scheduling rule. It instructs the Kubernetes scheduler to avoid co-locating multiple Postgres pods from the same cluster on the same physical node. This ensures that a single node failure cannot take down your entire database cluster.

Planning for Disaster Recovery

High availability protects against failures within a single cluster or availability zone. Disaster recovery addresses the loss of an entire data center or region. This requires a strategy centered around off-site backups.

The industry-standard strategy for PostgreSQL DR is continuous archiving using tools like pg_basebackup combined with a WAL archiving tool such as WAL-G or pgBackRest. This methodology consists of two components:

- Full Base Backup: A complete physical copy of the database, taken periodically (e.g., daily).

- Continuous WAL Archiving: As WAL segments are generated by the primary, they are immediately streamed to a durable, remote object storage service (e.g., AWS S3, Google Cloud Storage, Azure Blob Storage).

This combination enables Point-in-Time Recovery (PITR). In a disaster scenario, you can restore the most recent full backup and then replay the archived WAL files to recover the database state to any specific moment, minimizing data loss.

PostgreSQL's immense popularity is driven by its powerful and extensible feature set. As of 2025, it commands 16.85% of the relational database market, serving as the data backbone for organizations like Spotify and NASA. Its advanced capabilities, from JSONB and PostGIS to vector support for AI/ML applications, fuel its growing adoption. More details on this trend are available in the rising popularity of PostgreSQL on experience.percona.com. For a system this critical running on Kubernetes, a well-architected DR plan is not optional.

Securing Your Database With Essential Networking Patterns

Securing your postgres on kubernetes deployment requires a multi-layered, defense-in-depth strategy. In a dynamic environment where pods are ephemeral, traditional network security models based on static IP addresses are insufficient. You must adopt a cloud-native approach that combines network policies with strict access control.

The first step is controlling network exposure of the database. Kubernetes provides several Service types for this purpose, each serving a distinct use case.

Controlling Database Exposure

The most secure and recommended method for exposing Postgres is using a ClusterIP service. This is the default service type, which assigns a stable virtual IP address that is only routable from within the Kubernetes cluster. This effectively isolates the database from any external network traffic. For the vast majority of use cases, where only in-cluster applications need to connect to the database, this is the correct choice.

If external access is an absolute requirement, you can use a LoadBalancer service. This provisions an external load balancer from your cloud provider (e.g., an AWS ELB or a Google Cloud Load Balancer) that routes traffic to your Postgres service. This approach should be used with extreme caution, as it exposes the database directly to the public internet. If you use it, you must implement strict firewall rules (security groups) and enforce mandatory TLS encryption for all connections.

Enforcing Zero-Trust With NetworkPolicies

By default, Kubernetes has a flat network model where any pod can communicate with any other pod. A zero-trust security model assumes no implicit trust and requires explicit policies to allow communication. This is implemented using NetworkPolicy resources. A NetworkPolicy acts as a micro-firewall for your pods, allowing you to define granular ingress and egress rules.

A well-defined

NetworkPolicyis your most effective tool for preventing lateral movement by an attacker. If an application pod is compromised, a strict policy can prevent it from connecting to the database, thus containing the breach.

For instance, you can create a policy that only allows ingress traffic to your Postgres pod on port 5432 from pods with the label app: my-api. All other connection attempts will be blocked at the network level. This "principle of least privilege" is a cornerstone of modern security architecture.

For a comprehensive overview, refer to our guide on Kubernetes security best practices.

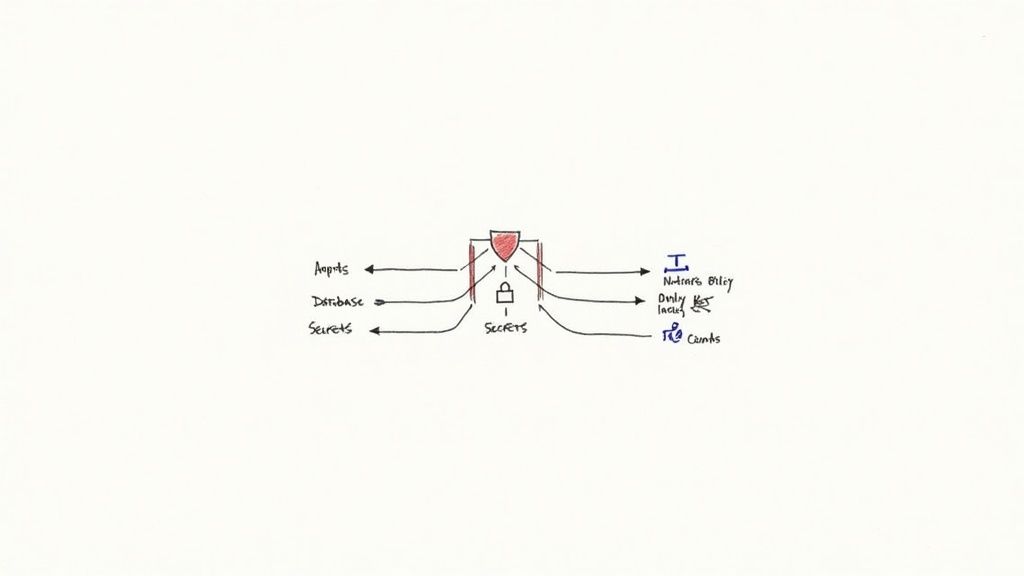

Managing Secrets And Access Control

Hardcoding database credentials in application code, configuration files, or container images is a severe security vulnerability. The correct method for managing sensitive information is using Kubernetes Secrets. A Secret is an API object designed to hold confidential data, which can then be securely mounted into application pods as environment variables or files in a volume.

However, network security is only one part of the equation. Application-level vulnerabilities must also be addressed. A primary threat to databases is preventing SQL injection attacks, which can bypass network controls entirely.

Finally, access to both the database itself and the Kubernetes resources that manage it must be tightly controlled.

- Role-Based Access Control (RBAC): Use Kubernetes RBAC to enforce the principle of least privilege, controlling which users or service accounts can interact with your database pods, services, and secrets.

- Postgres Roles: Within the database, create specific user roles with the minimum set of privileges required for each application. The superuser account should never be used for routine application connections.

- Transport Layer Security (TLS): Enforce TLS encryption for all connections between your applications and the Postgres database. This prevents man-in-the-middle attacks and ensures data confidentiality in transit.

Implementing Robust Monitoring and Performance Tuning

Operating a database without comprehensive monitoring is untenable. When running Postgres on Kubernetes, the dynamic nature of the environment makes robust observability a critical requirement. The goal is not just to detect failures but to proactively identify performance bottlenecks and resource constraints. The de facto standard monitoring stack in the cloud-native ecosystem is Prometheus for metrics collection and Grafana for visualization.

To integrate Prometheus with PostgreSQL, a metrics exporter is required. The postgres_exporter is a widely used tool that runs as a sidecar container alongside your database pod. It queries PostgreSQL's internal statistics views (e.g., pg_stat_database, pg_stat_activity) and exposes the metrics in a format that Prometheus can scrape.

Key Postgres Metrics to Track

Effective monitoring requires focusing on key performance indicators (KPIs) that provide actionable insights into the health and performance of your database.

Here are the essential metrics to monitor:

- Transaction Throughput:

pg_stat_database_xact_commit(commits) andpg_stat_database_xact_rollback(rollbacks). These metrics indicate the database workload. A sudden increase in rollbacks often signals application-level errors. - Replication Lag: For HA clusters, monitoring the lag between the primary and replica nodes is critical. A consistently growing lag indicates that replicas are unable to keep up with the primary's write volume, jeopardizing your RPO and RTO for failover.

- Cache Hit Ratio: This metric indicates the percentage of data blocks read from PostgreSQL's shared buffer cache versus from disk. A cache hit ratio consistently below 99% suggests that the database is memory-constrained and may benefit from a larger

shared_buffersallocation. - Index Efficiency: Monitor the ratio of index scans (

idx_scan) to sequential scans (seq_scan) from thepg_stat_user_tablesview. A high number of sequential scans on large tables is a strong indicator of missing or inefficient indexes.

Monitoring is the process of translating raw data into actionable insights. By focusing on these core metrics, you can shift from a reactive, "fire-fighting" operational posture to a proactive, performance-tuning one. Learn more about implementing this in our guide on Prometheus service monitoring.

Tuning Performance in a Kubernetes Context

Performance tuning in Kubernetes involves both traditional database tuning and configuring the pod's interaction with the cluster's resource scheduler.

The most critical pod specification settings are resource requests and limits.

- Requests: The amount of CPU and memory that Kubernetes guarantees to your pod. This is a reservation that ensures your database has the minimum resources required to function properly.

- Limits: The maximum amount of CPU and memory the pod is allowed to consume. Setting a memory limit is crucial to prevent a memory-intensive query from consuming all available memory on a node, which could lead to an Out-of-Memory (OOM) kill and instability across the node.

For a stateful workload like a database, it is best practice to set resource requests and limits to the same value. This places the pod in the Guaranteed Quality of Service (QoS) class. Guaranteed QoS pods have the highest scheduling priority and are the last to be evicted during periods of node resource pressure, providing maximum stability for your database.

Postgres on Kubernetes: Your Questions Answered

Deploying a stateful system like PostgreSQL on an ephemeral platform like Kubernetes naturally raises questions. Addressing these concerns with clear, technical answers is crucial for building a reliable and supportable database architecture.

Is This Really a Good Idea for Production?

Yes, unequivocally. Running production databases on Kubernetes has evolved from an experimental concept to a mature, industry-standard practice, provided it is implemented correctly. The platform's native constructs, such as StatefulSets and the Persistent Storage subsystem, provide the necessary foundation. When combined with a production-grade database Operator, the architecture becomes robust and reliable.

The key is to move beyond simply containerizing Postgres. An Operator provides automated management for critical day-2 operations: high-availability failover, point-in-time recovery, and controlled version upgrades. This level of automation significantly reduces the risk of human error, which is a leading cause of outages in manually managed database systems.

What's the Single Biggest Mistake to Avoid?

The most common mistake is underestimating the operational complexity of a manual deployment. It is deceptively easy to create a basic StatefulSet and a PVC, but this initial simplicity ignores the long-term operational burden.

A manual setup without a rigorously tested, automated plan for backups, failover, and upgrades is not a production solution; it is a future outage waiting to happen.

This is precisely why leveraging a mature Kubernetes Operator is the recommended approach for production workloads. It encapsulates years of operational best practices into a reliable, automated system, allowing your team to focus on application development rather than infrastructure management.

How Should We Handle Connection Pooling?

Connection pooling is not optional; it is a mandatory component for any high-performance Postgres deployment on Kubernetes. PostgreSQL's process-per-connection model can be resource-intensive, and the dynamic nature of a containerized environment can lead to a high rate of connection churn.

The standard pattern is to deploy a dedicated connection pooler like PgBouncer between your applications and the database. There are two primary deployment models for this:

- Sidecar Container: Deploy PgBouncer as a container within the same pod as your application. This isolates the connection pool to each application replica.

- Standalone Service: Deploy PgBouncer as a separate, centralized service that all application replicas connect to. This model is often simpler to manage and monitor at scale.

Many Kubernetes Operators can automate the deployment and configuration of PgBouncer, ensuring that your database is protected from connection storms and can scale efficiently.

At OpsMoon, we specialize in designing, building, and managing robust, scalable infrastructure on Kubernetes. Our DevOps experts can architect a production-ready Postgres on Kubernetes solution tailored to your specific performance and availability requirements. Let's build your roadmap together—start with a free work planning session.