Best Guide: microservices vs monolithic architecture for developers

Discover how microservices vs monolithic architecture affect scalability, deployment, and operations, and learn which approach best fits your project.

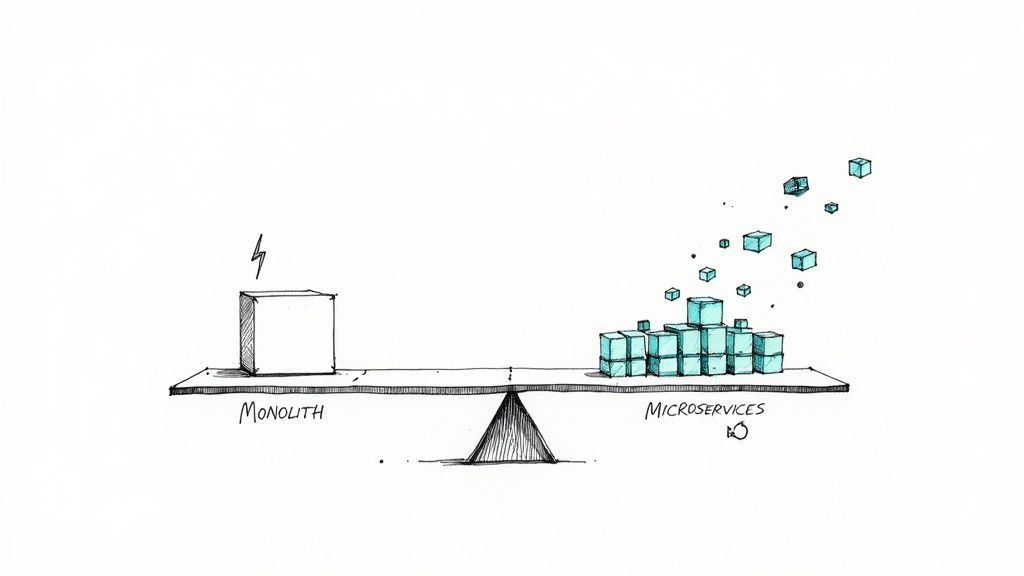

At its core, the microservices vs. monolithic architecture debate is a fundamental engineering trade-off: a monolithic architecture collocates all application components into a single, deployable unit with in-process communication, while a microservices architecture decomposes the application into a collection of independently deployable, network-connected services. It's a choice between the initial development velocity of a monolith and the long-term scalability and organizational agility of microservices.

Choosing Your Architectural Foundation

Selecting between a monolithic and a microservices architecture is one of the most consequential decisions in the software development lifecycle. It's not a superficial choice; it dictates your application's deployment topology, team structure, CI/CD pipeline complexity, and long-term scalability profile. This isn't about choosing one large executable versus many small ones—it's about committing to a specific operational model and development culture.

To make an informed decision, you must have a firm grasp of software architecture fundamentals.

A monolithic application is a single, self-contained unit where the user interface, business logic, and data access layer are tightly coupled within a single codebase and deployed as one artifact (e.g., a WAR, JAR, or executable). For greenfield projects, particularly for startups launching a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), the simplicity of a single codebase, a unified build process, and a straightforward deployment strategy offers a significant time-to-market advantage.

Conversely, a microservices architecture structures an application as a suite of loosely coupled, fine-grained services. Each service is organized around a specific business capability, encapsulates its own data persistence, and can be developed, deployed, and scaled independently. This model is foundational to modern cloud-native application development, delivering the resilience, technological heterogeneity, and granular scalability required for complex systems.

The core trade-off is this: monoliths offer low initial complexity and high development velocity, while microservices provide long-term operational flexibility, fault isolation, and independent scalability at the cost of increased infrastructural and cognitive overhead. Understanding this distinction is the first step toward selecting the optimal architecture for your technical and business context.

Quick Comparison Monolithic vs Microservices Architecture

To establish a baseline for a more technical analysis, this table outlines the key architectural differences and their practical implications.

| Criterion | Monolithic Architecture | Microservices Architecture |

|---|---|---|

| Codebase Structure | Single, unified codebase (monorepo). Components are modules or packages. | Multiple, independent codebases, typically one per service. |

| Deployment Unit | The entire application is deployed as a single artifact. | Each service is an independently deployable artifact. |

| Scalability | Scaled vertically (more resources per node) or horizontally by replicating the entire monolith. | Services are scaled independently based on specific resource demands (e.g., CPU, memory). |

| Technology Stack | Homogeneous; a single technology stack (e.g., Spring Boot, Ruby on Rails) is used across the application. | Heterogeneous; services can be implemented in different languages and frameworks (polyglot persistence). |

| Team Structure | Often managed by a single, large development team, leading to coordination overhead (Conway's Law). | Suited for smaller, autonomous teams aligned with specific business domains. |

| Initial Complexity | Low; simpler to set up local environments, IDEs, and initial CI/CD pipelines. | High; requires service discovery, API gateways, and complex inter-service communication protocols. |

| Fault Isolation | Low; an uncaught exception or resource leak in one module can degrade or crash the entire application. | High; failure in one service is isolated and can be handled with patterns like circuit breakers. |

While this table provides a high-level overview, the real impact is in the implementation details. Each of these points has profound consequences for your operational budget, developer productivity, and ability to innovate.

Anatomy Of The Monolithic Architecture

A monolithic architecture is implemented as a single, large-scale application where all functional components are tightly coupled within a single process. Think of it as a self-contained system where every part—from the front-end UI rendering to the back-end business logic and the data persistence layer—is compiled, packaged, and deployed as a single unit. This unified model is the traditional and often default choice for new applications due to its straightforward development and deployment model.

This structure provides tangible operational benefits, particularly for smaller engineering teams. With a single codebase, onboarding new developers is streamlined, and debugging is often less complex. Tracing a request from the UI to the database involves following a single call stack within a single process, eliminating the need for complex distributed tracing tools required by microservices.

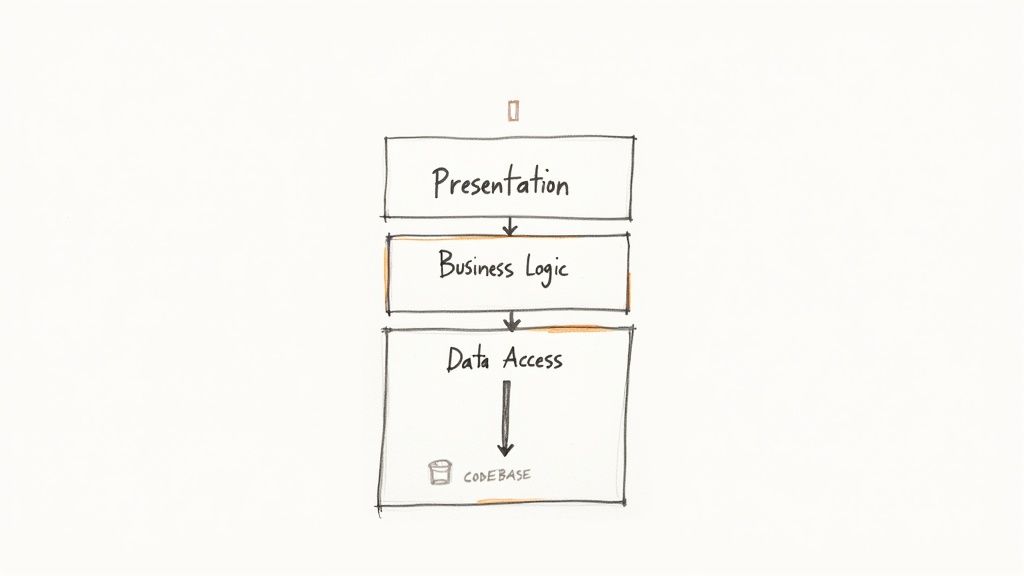

The Three-Tier Internal Structure

Most monolithic applications adhere to a classic three-tier architectural pattern to enforce logical separation of concerns. While these layers are logically distinct, they remain physically collocated within the same deployment artifact.

- Presentation Layer: This is the top-most layer, responsible for handling HTTP requests and rendering the user interface. In a web application, this layer contains UI components (e.g., Servlets, JSPs, or controllers in an MVC framework) that generate the HTML, CSS, and JavaScript sent to the client's browser.

- Business Logic Layer: This is the core of the application where domain logic is executed. It processes user inputs, orchestrates data access, enforces business rules, and implements the application's primary functions. For an e-commerce monolith, this layer would contain the logic for inventory management, order processing, and payment validation.

- Data Access Layer (DAL): This layer acts as an abstraction between the business logic and the physical database. It encapsulates the logic for all Create, Read, Update, and Delete (CRUD) operations, often using an Object-Relational Mapping (ORM) framework like Hibernate or Entity Framework.

This layered structure provides a clear separation of concerns initially, but as the application grows, the boundaries between these layers often erode, leading to a "big ball of mud"—a system with high coupling and low cohesion.

Operational Benefits And Scaling Challenges

The initial advantages of a monolith are clear, but the trade-offs become severe as the application scales. While the infrastructure is simple to manage at first (a single application server and a database), growing code complexity can dramatically slow down development cycles. A small change in one module can have unintended consequences across the system, necessitating extensive regression testing and increasing the risk of deployment failures.

Key Takeaway: The primary challenge with a monolith is not its initial simplicity but its escalating complexity over time. As the codebase grows, technological lock-in becomes a significant risk, and refactoring or adopting new technologies without disrupting the entire application becomes nearly impossible.

This scaling friction is where the microservices vs monolithic architecture debate intensifies. Empirical data reveals a pragmatic industry trend: many organizations begin with a monolith and only migrate when scale or team size dictates. Monoliths accelerate initial deployment, but their efficiency diminishes as development teams exceed 10 to 15 engineers. While microservices are superior for scaling teams, they increase operational complexity by 3 to 5 times and require 5 to 10 times more sophisticated infrastructure. You can read more about the pragmatic trade-offs between monoliths and microservices.

Ultimately, the anatomy of a monolith is one of unified strength that can evolve into a single point of failure and a significant bottleneck to innovation. Understanding these structural limitations is key to recognizing when to evolve beyond this architecture.

Deconstructing The Microservices Architecture

In stark contrast to a monolith's integrated design, a microservices architecture decomposes an application into a collection of independently deployable services. Each service is designed around a specific business capability, maintains its own codebase and data store, and can be developed, tested, deployed, and scaled autonomously.

This architecture is fundamentally decentralized and promotes loose coupling, providing engineering teams with significant flexibility and autonomy.

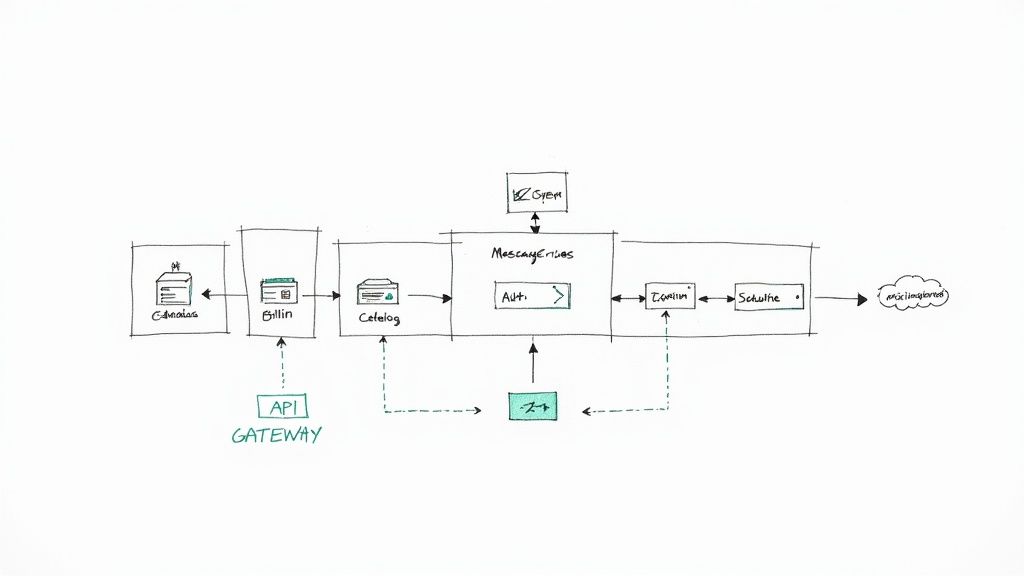

This represents a paradigm shift from the monolithic model. Instead of a single application handling all functionality, you have discrete services for user authentication, payment processing, inventory management, and shipping. These services communicate with each other over the network, typically via APIs, forming a distributed system that is both powerful and inherently complex. To manage this complexity, several critical infrastructure components are required.

Core Components And Communication Patterns

At the heart of any microservices architecture is the need for robust and reliable inter-service communication. This introduces essential infrastructure that is absent in a monolithic world.

- API Gateway: This component acts as a single entry point for all client requests. The gateway routes requests to the appropriate downstream microservice, abstracting the internal service topology from clients. It is also the ideal location to implement cross-cutting concerns such as SSL termination, authentication, rate limiting, and caching.

- Service Discovery: In a dynamic environment where service instances are ephemeral and scale up or down, a mechanism is needed for services to locate each other. A service discovery component (e.g., Consul, Eureka) acts as a dynamic registry, maintaining the network locations of all service instances.

- Inter-service Communication: Services must communicate over the network. This typically occurs via two primary patterns: synchronous communication using protocols like REST over HTTP or gRPC for direct request-response interactions, or asynchronous communication using message brokers (e.g., RabbitMQ, Apache Kafka) for event-driven workflows where services publish and subscribe to events.

With numerous moving parts, defining clear API contracts (e.g., using OpenAPI or Protocol Buffers) and adhering to solid API development best practices is non-negotiable. This structured communication is what enables the distributed system to function cohesively.

The real power of microservices lies in independent scalability and fault isolation. If the payment service experiences a surge in traffic, you can scale only that service horizontally without affecting other services. Similarly, if a non-critical service fails, the system can degrade gracefully without a catastrophic failure of the entire application.

Benefits And Emerging Realities

The promise of enhanced modularity and scalability has driven widespread adoption, with up to 85% of large organizations adopting microservices. However, it is not a panacea. The operational reality, particularly challenges with network latency and distributed system complexity, has led some prominent companies, like Amazon Prime Video, to reconsider and move certain components back to a monolithic structure.

This has fueled interest in the "modular monolith"—a single deployable application with strong, well-enforced internal boundaries—as a more pragmatic alternative. This trend underscores that the architectural choice is highly context-dependent, hinging on scale, team structure, and business objectives.

Another significant benefit is technology heterogeneity, which allows teams to select the optimal technology stack for each service. You can delve deeper into this in our comprehensive guide to microservices architecture design patterns.

While this architecture supports massive scale and parallel development, it introduces the inherent complexity of distributed systems, which we will now explore in detail.

Technical Trade-Offs In Development And Operations

When evaluating microservices vs. monolithic architecture from an engineering perspective, the most significant differences manifest in the day-to-day development and operational workflows. This architectural choice is not a one-time decision; it fundamentally shapes how teams write code, build and test software, and manage production systems. Each approach presents a distinct set of technical trade-offs that impact everything from developer productivity to system reliability.

For any engineering leader, a deep understanding of these granular details is critical. An architecture that appears elegant on a whiteboard can introduce immense friction if it misaligns with the team's skillset, operational maturity, or the product's long-term roadmap. Let's dissect the key areas where these two architectures diverge.

Development Workflow And Team Structure

In a monolith, development is centralized. The entire team works within a single large codebase, which simplifies cross-cutting changes. A developer can modify a database schema, update the business logic that consumes it, and adjust the UI in a single atomic commit.

This integrated structure is highly effective for small, collocated teams where informal communication is sufficient for coordination. However, as the team and codebase grow, this advantage erodes. Merge conflicts become frequent, build times extend from minutes to hours, and onboarding new engineers becomes a formidable task, as they must comprehend the entire system's complexity.

Microservices champion decentralized development. Each service is owned by a small, autonomous team. This structure enables teams to develop, test, and deploy in parallel with minimal cross-team dependencies, dramatically increasing feature velocity for large organizations. A team can iterate on its service, run its isolated test suite, and deploy to production independently.

Key Consideration: The fundamental trade-off is between coordination simplicity and development velocity. Monoliths simplify coordination for small teams at the cost of potential future bottlenecks. Microservices enable parallel, high-velocity development for larger organizations but introduce the overhead of formal inter-team communication and API contract management.

CI/CD Pipelines And Deployment Complexity

Deployment is perhaps the most starkly contrasting aspect. With a monolith, the process is conceptually simple: build the entire application into a single artifact, execute a comprehensive test suite, and deploy the unit. While straightforward, this process is brittle and slow. A minor change in a single module requires a full redeployment of the entire application, introducing risk and creating a release train that can block critical updates.

Microservices, conversely, necessitate a sophisticated Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery (CI/CD) model. Each service has its own independent deployment pipeline, allowing it to be built, tested, and deployed without impacting other services. This enables rapid, incremental updates and significantly reduces the blast radius of a failed deployment.

However, this independence introduces significant operational challenges:

- Pipeline Sprawl: Managing and maintaining dozens or hundreds of separate CI/CD pipelines requires substantial automation and tooling.

- Version Management: Tracking dependencies between services and ensuring compatibility between different service versions (e.g., using consumer-driven contract testing) is a complex problem.

- Orchestration: Container orchestration platforms like Kubernetes become essential for managing the deployment, scaling, networking, and health of a fleet of distributed services.

Scalability And Performance Characteristics

A monolith is typically scaled horizontally by deploying multiple instances of the entire application behind a load balancer. This approach is effective but often inefficient. If only a single, computationally intensive feature (e.g., video transcoding) is experiencing high load, the entire application must be scaled, wasting resources on idle components.

Microservices provide granular scalability, a key advantage. If the user authentication service is under heavy load, only that service needs to be scaled by increasing its instance count. This targeted scaling is highly resource-efficient and cost-effective, allowing for precise allocation of infrastructure resources.

The trade-off is performance overhead. Every inter-service call is a network request, which introduces latency and is inherently less reliable than an in-process method call within a monolith. This network latency can accumulate in complex call chains, and poorly designed service interactions can create performance bottlenecks and cascading failures that are difficult to debug.

Data Management And Fault Tolerance

In a monolith, data management is simplified by a single, shared database that guarantees strong transactional consistency (ACID properties). This makes it easy to implement operations that span multiple domain entities while ensuring data integrity.

Microservices advocate for decentralized data management, where each service owns its own private database. This grants teams autonomy and prevents the database from becoming a performance bottleneck or a single point of failure. However, it introduces significant new challenges:

- Data Consistency: Maintaining data consistency across multiple distributed databases requires implementing complex patterns like the Saga pattern to manage eventual consistency.

- Distributed Transactions: Implementing atomic transactions that span multiple services is extremely difficult and often discouraged in favor of idempotent, compensating actions.

- Complex Queries: Joining data across different services requires building API composition layers or implementing data aggregation patterns like Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS).

This division also impacts fault tolerance. A critical failure in a monolith, such as a database connection pool exhaustion, can bring the entire application down. A well-designed microservices system, however, provides superior fault isolation. If a non-essential service (e.g., a recommendation engine) fails, the core application can continue to function, enabling graceful degradation rather than a total outage.

Detailed Technical Trade-Offs Monolith vs Microservices

| Technical Aspect | Monolithic Approach | Microservices Approach | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Codebase Management | Single, large repository. Easier for small teams to coordinate. | Multiple repositories, one per service. Promotes team autonomy. | Merge conflicts and build times increase with team size in a monolith. |

| Development Velocity | Slower over time as complexity grows; changes are coupled. | Faster for individual teams; parallel development is possible. | Requires strong API contracts and communication to avoid integration chaos. |

| CI/CD Pipeline | Single, complex pipeline. A failure blocks the entire release. | Independent pipeline per service. Enables rapid, isolated deployments. | Operational overhead of managing many pipelines is significant. |

| Scalability | Scaled as a single unit. Often inefficient and costly. | Granular scaling of individual services. Highly efficient. | Network latency between services can become a performance bottleneck. |

| Data Consistency | Strong consistency (ACID) via a shared database. Simple. | Eventual consistency is the norm. Requires complex patterns. | Business requirements for transactional integrity are a critical factor. |

| Fault Isolation | Low. A failure in one module can crash the entire application. | High. Failure of one service won't bring down others. | Requires robust resiliency patterns like circuit breakers and retries. |

| Onboarding | Difficult. New developers must understand the entire system. | Easier. A developer only needs to learn a single service's context. | Understanding the overall system architecture becomes more abstract. |

| Technology Stack | One standardized stack for the entire application. | Polyglot. Teams can choose the best tech for their service. | Managing and securing multiple technology stacks adds complexity. |

This table underscores that there is no universally "correct" answer. The optimal choice is deeply contextual, depending on your team's size and expertise, your operational capabilities, and the specific technical challenges you aim to solve.

Making The Right Architectural Choice

So, how do you translate these technical trade-offs into a definitive decision for your project? The process must be pragmatic and grounded in an honest assessment of your organization's current capabilities and future needs. The "right" architecture is the one that aligns with your team size, product complexity, scalability targets, and operational maturity.

Adopting microservices before your team and infrastructure are ready can lead to a distributed monolith—a worst-of-both-worlds scenario. Conversely, sticking with a monolith for too long can stifle growth and innovation. Making an informed decision requires asking critical, context-specific questions.

A Practical Decision Checklist

Before committing to an architectural path, use this checklist to evaluate your specific situation. The answers will guide you toward either the operational simplicity of a monolith or the granular control of microservices.

- Team Size and Structure: What is the current and projected size of your engineering team? Are you a single, co-located team, or distributed autonomous squads? (Conway's Law)

- Domain Complexity: Is your application's business domain relatively simple and cohesive, or is it composed of multiple complex, loosely related subdomains?

- Scalability Requirements: Do you anticipate uniform load across the application, or will specific functionalities require independent, elastic scaling to handle load spikes?

- Operational Maturity: Does your team have deep expertise in CI/CD, container orchestration (like Kubernetes), distributed monitoring, and infrastructure-as-code?

- Speed to Market: Is the primary business driver to ship an MVP as quickly as possible to validate a market, or are you building a long-term, highly scalable platform?

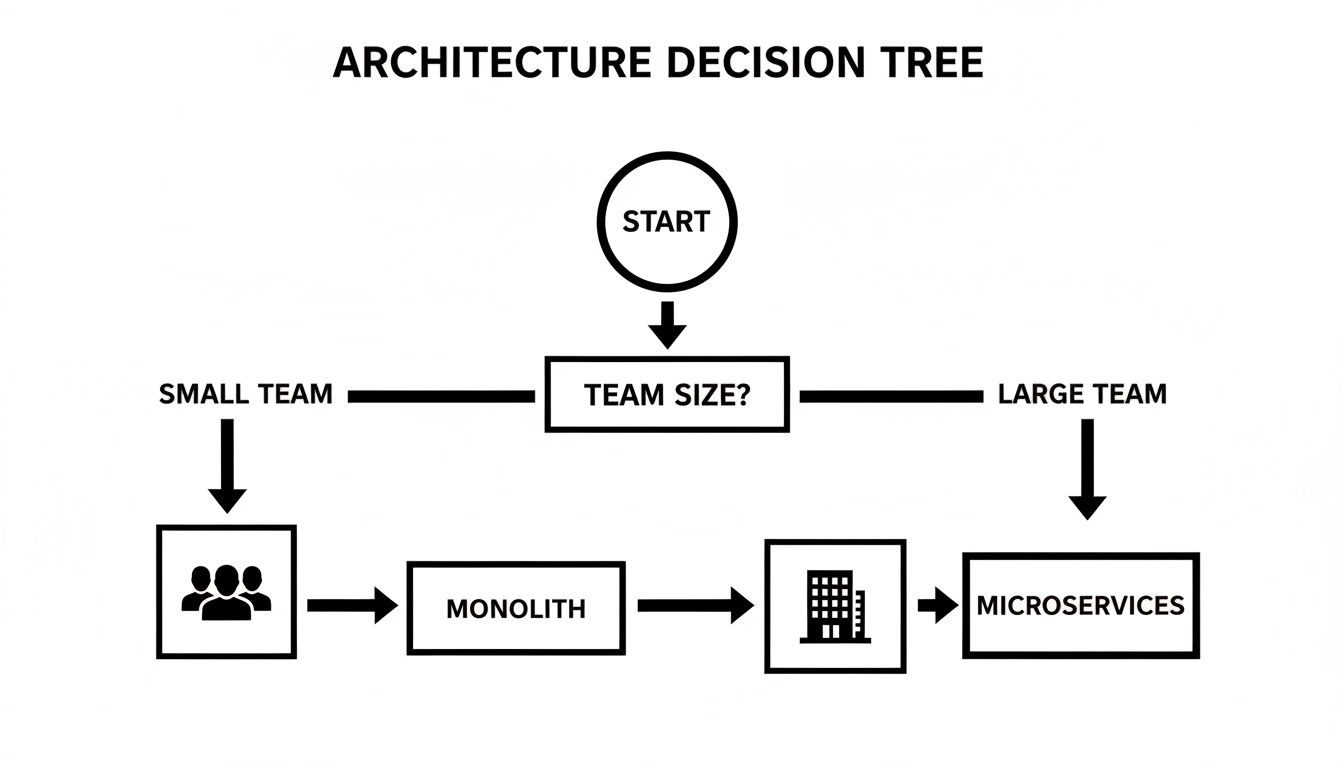

This flowchart illustrates how a single factor—team size—can heavily influence the decision.

This visualizes a core principle: smaller teams benefit from a monolith's reduced cognitive and operational load, while larger organizations can leverage microservices to minimize coordination overhead and maximize parallel development.

When To Choose A Monolith

Despite the industry's focus on distributed systems, a monolithic architecture remains the most pragmatic choice for many scenarios. Its low initial complexity and minimal operational overhead are decisive advantages under the right conditions.

A monolith is often your best bet for:

- Startups and MVPs: When time-to-market is critical, a monolith enables a small team to build and deploy a functional product rapidly, without the distraction of managing a complex distributed system.

- Simple Applications: For applications with a limited and well-defined scope (e.g., a departmental CRUD application or a simple content management system), the overhead of microservices is unjustifiable.

- Small, Co-located Teams: If your entire engineering team can easily coordinate and has a shared understanding of the codebase, the simplicity of a single repository and deployment process is highly efficient.

A monolith isn’t a legacy choice; it’s a strategic one. For an early-stage product, it is often the most capital-efficient path to market validation, preserving engineering resources for when scaling challenges become a reality.

When To Justify Microservices

The significant investment in infrastructure, tooling, and specialized expertise required by microservices is only justified when the problems they solve—such as scaling bottlenecks, slow development velocity, and organizational complexity—are more costly than the complexity they introduce.

Consider microservices for:

- Large-Scale Platforms: For applications with high traffic volumes and complex user interactions (e.g., e-commerce platforms, streaming services), the ability to independently scale and deploy components is a necessity.

- Complex Business Domains: When an application comprises multiple distinct and complex business capabilities, microservices help manage this complexity by enforcing strong boundaries and allowing for specialized implementations.

- Large Engineering Organizations: Microservices align with organizational structures that feature multiple autonomous teams, enabling them to work on different parts of the application in parallel, thereby accelerating development velocity at scale.

The Middle Ground: A Modular Monolith

For teams caught between these two architectural poles, the Modular Monolith offers a compelling hybrid solution. This approach involves building a single, deployable application while enforcing strict, logical boundaries between different modules within the codebase, often using language-level constructs like Java modules or .NET assemblies.

Each module is designed as if it were a separate service, with well-defined public APIs and no direct dependencies on the internal implementation of other modules. This model provides many of the benefits of microservices—such as improved code organization and clear separation of concerns—without the significant operational overhead of a distributed system. It also provides a clear and low-risk migration path for the future; well-encapsulated modules are far easier to extract into independent microservices when the need arises.

Migrating From Monolith To Microservices

Migrating from a monolith to a microservices architecture is a major undertaking that requires a meticulous and strategic approach. A "big bang" rewrite, where the entire application is rebuilt from scratch, is a high-risk strategy that rarely succeeds due to its long development timeline, delayed value delivery, and the immense challenge of keeping the new system in sync with the evolving legacy one.

An incremental migration is the only viable path. This involves gradually decomposing the monolith by extracting functionality into new, independent microservices. This iterative approach allows for continuous value delivery, reduces risk, and keeps the existing application operational throughout the process.

Adopting The Strangler Fig Pattern

The Strangler Fig Pattern is a widely adopted, battle-tested strategy for incremental migration. The pattern involves building a new system around the edges of the old one, gradually intercepting and replacing its functionality until the old system is "strangled" and can be decommissioned.

The process begins by placing a reverse proxy or an API gateway in front of the monolith, which initially routes all traffic to the legacy application. Next, you identify a specific, well-bounded piece of functionality to extract—for example, user authentication. You then build this functionality as a new, independent microservice.

Once the new service is developed and tested, you configure the gateway to route all authentication-related requests to the new microservice instead of the monolith. This process is repeated for other functionalities, one service at a time, until the monolith's responsibilities have been fully taken over by the new microservices.

The primary benefit of the Strangler Fig Pattern is risk mitigation. It allows you to validate each new service in a production environment independently, without the immense pressure of a single, high-stakes cutover. This transforms a daunting migration into a series of manageable, iterative steps.

Key Technical Challenges In Migration

A successful migration requires addressing several complex technical challenges head-on. Failure to do so can result in a "distributed monolith"—an anti-pattern that combines the distributed systems complexity of microservices with the tight coupling of a monolith.

Key challenges include:

- Identifying Service Boundaries: Defining the correct boundaries for each microservice is critical. This process should be driven by business domains, not just technical considerations. Domain-Driven Design (DDD) is the standard methodology here, helping to identify "bounded contexts" that map cleanly to independent services with high cohesion and loose coupling.

- Managing Data Consistency: Extracting a service often means disentangling its data from a large, shared monolithic database. This immediately introduces challenges with data consistency across distributed systems. You will need to implement patterns like event-driven architectures, change data capture (CDC), or the Saga pattern to manage transactions that now span multiple services and databases.

- Infrastructure and Observability: You are not just building services; you are building a platform to run them. This requires an API gateway for traffic management, a service discovery mechanism, and a robust observability stack. Centralized logging (e.g., ELK stack), distributed tracing (e.g., Jaeger, OpenTelemetry), and comprehensive monitoring and alerting are non-negotiable for debugging and operating a complex distributed system effectively.

This process shares many similarities with other large-scale modernization efforts. For a deeper technical dive into planning and execution, see our guide on legacy system modernisation. Addressing these challenges proactively is what distinguishes a successful migration from a costly failure.

Got Questions? We've Got Answers

Choosing an architecture invariably raises numerous practical questions. Here are answers to the most common technical queries from teams deliberating the microservices vs monolithic architecture trade-off.

When Is A Monolith Actually Better Than Microservices?

A monolith is technically superior for early-stage projects, MVPs, and small teams where development velocity and simplicity are paramount. Its single-process architecture eliminates the network latency and distributed systems complexity inherent in microservices, resulting in simpler debugging, testing, and deployment workflows.

If your application domain is not overly complex and does not have disparate scaling requirements for its features, the operational simplicity of a monolith provides a significant advantage. The reduced cognitive overhead and lower infrastructure costs make it a more efficient and pragmatic starting point.

What's The Single Biggest Hurdle In Adopting Microservices?

From a technical standpoint, the single biggest hurdle is managing the immense increase in operational complexity. You are no longer managing a single application; you are operating a complex distributed system. This requires deep expertise in service discovery, API gateways, distributed tracing, centralized logging, container orchestration, and sophisticated CI/CD pipelines.

The core challenge is not just adopting new tools but fostering a DevOps culture. Your team must be prepared for the significant overhead of monitoring, debugging, and maintaining a fleet of independent services, which requires a fundamentally different skillset and mindset compared to managing a single monolithic application.

Can You Mix and Match Architectures?

Absolutely. A hybrid architecture is not only feasible but often the most pragmatic long-term strategy. Starting with a monolith allows for rapid initial development. As the application and team grow, you can strategically decompose the monolith by extracting specific functionalities into microservices using a controlled approach like the Strangler Fig Pattern.

This allows you to isolate high-load, frequently changing, or business-critical features into their own services, reaping the benefits of microservices where they provide the most value. Meanwhile, the stable, less-volatile core of the application can remain as a monolith. This iterative approach balances innovation speed with operational stability, avoiding the high risk of a "big bang" rewrite.

Ready to build a rock-solid DevOps strategy for whichever path you choose? OpsMoon will connect you with elite remote engineers who live and breathe scalable systems. Book a free work planning session to map out your infrastructure and find the exact talent you need to move faster.