The Difference Between Docker and Kubernetes: A Technical Deep-Dive

Explore the difference between docker and kubernetes: a clear, concise comparison of architectures, workflows, and when to use each.

Engineers often frame the discussion as "Docker vs. Kubernetes," which is a fundamental misunderstanding. They are not competitors; they are complementary technologies that solve distinct problems within the containerization lifecycle. The real conversation is about how they integrate to form a modern, cloud-native stack.

In short: Docker is a container runtime and toolset for building and running individual OCI-compliant containers, while Kubernetes is a container orchestration platform for automating the deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications across a cluster of nodes. Docker creates the standardized unit of deployment—the container image—and Kubernetes manages those units in a distributed production environment.

Defining Roles: Docker vs. Kubernetes

Pitting them against each other misses their distinct scopes. Docker operates at the micro-level of a single host. Its primary function is to package an application with its dependencies—code, runtime, system tools, system libraries—into a lightweight, portable container image. This standardized artifact solves the classic "it works on my machine" problem by ensuring environmental consistency from development to production.

Kubernetes (K8s) operates at the macro-level of a cluster. Once you have built your container images, Kubernetes takes over to run them across a fleet of machines (nodes). It abstracts away the underlying infrastructure and handles the complex operational challenges of running distributed systems in production.

These challenges include:

- Automated Scaling: Dynamically adjusting the number of running containers (replicas) based on real-time metrics like CPU or memory utilization.

- Self-Healing: Automatically restarting crashed containers, replacing failed containers, and rescheduling workloads from failed nodes to healthy ones.

- Service Discovery & Load Balancing: Providing stable network endpoints (Services) for ephemeral containers (Pods) and distributing traffic among them.

- Automated Rollouts & Rollbacks: Managing versioned deployments, allowing for zero-downtime updates and immediate rollbacks if issues arise.

To use a technical analogy: Docker provides the

chrootjail with process isolation via namespaces and resource limiting via cgroups. Kubernetes is the distributed operating system that schedules these isolated processes across a cluster, managing their state, networking, and storage.

Key Distinctions at a Glance

To be precise, this table breaks down the core technical and operational differences. Understanding these distinctions is the first step toward architecting a modern, scalable system.

| Aspect | Docker | Kubernetes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Building OCI-compliant container images and running containers on a single host. | Automating deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications across a cluster. |

| Scope | Single host/node. The unit of management is an individual container. | A cluster of multiple hosts/nodes. The unit of management is a Pod (one or more containers). |

| Core Use Case | Application packaging (Dockerfile), local development environments, and CI/CD build agents. | Production-grade deployment, high availability, fault tolerance, and declarative autoscaling. |

| Complexity | Relatively low. The Docker CLI and docker-compose.yml are intuitive for single-host operations. |

High. A steep learning curve due to its distributed architecture and declarative API model. |

They fill two distinct but complementary roles. Docker is the de facto standard for containerization, with an 83.18% market share. Kubernetes has become the industry standard for container orchestration, with over 60% of enterprises adopting it for production workloads.

To gain a practical understanding of the containerization layer, this detailed Docker setup guide is an excellent starting point. It provides hands-on experience with the tooling that creates the artifacts Kubernetes is designed to manage.

Comparing Core Architectural Models

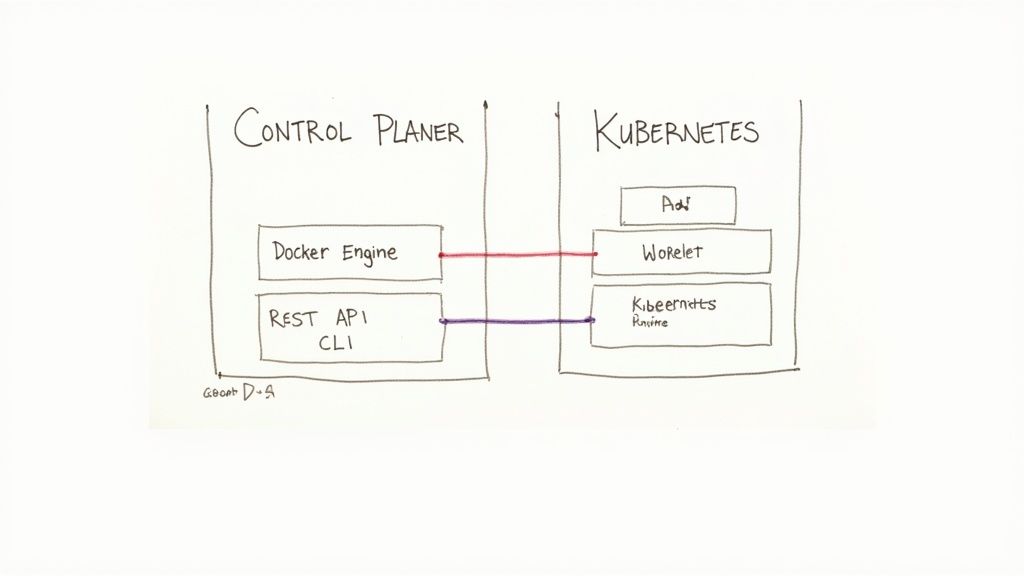

To grasp the fundamental separation between Docker and Kubernetes, one must analyze their architectural designs. Docker employs a straightforward client-server model optimized for a single host. In contrast, Kubernetes is a complex, distributed system architected for high availability and fault tolerance across a cluster.

Understanding these foundational blueprints is key to knowing why one tool builds containers and the other orchestrates them.

Deconstructing the Docker Engine

Docker's architecture is self-contained and centered on the Docker Engine, a core component installed on a host machine that manages all container lifecycle operations. Its design is laser-focused on its primary purpose: creating and managing individual containers efficiently on a single node.

The Docker Engine consists of three main components that form a classic client-server architecture:

- The Docker Daemon (

dockerd): This is the server-side, persistent background process that listens for Docker API requests. It manages Docker objects such as images, containers, networks, and volumes. It is the brain of the operation on a given host. - The REST API: The API specifies the interfaces that programs can use to communicate with the daemon. It provides a standardized programmatic way to instruct

dockerdon actions to perform, fromdocker buildtodocker stop. - The Docker CLI (Command Line Interface): When a user types a command like

docker run, they are interacting with the CLI client. The client takes the command, formats it into an API request, and sends it todockerdvia the REST API for execution.

This architecture is extremely effective for development and single-node deployments. Its primary limitation is its scope: it was fundamentally designed to manage resources on one host, not a distributed fleet.

Analyzing the Kubernetes Distributed System

Kubernetes introduces a far more intricate, distributed architecture designed for high availability and resilience. It utilizes a cluster model that cleanly separates management tasks (the Control Plane) from application workloads (the Worker Nodes). This architectural separation is precisely what enables Kubernetes to manage applications at massive scale.

A Kubernetes cluster is divided into two primary parts: the Control Plane and the Worker Nodes.

The architectural leap from Docker's single-host model to Kubernetes' distributed Control Plane and Worker Nodes is the core technical differentiator. It's the difference between managing a single process and orchestrating a distributed operating system.

The Kubernetes Control Plane Components

The Control Plane serves as the cluster's brain. It makes global decisions (e.g., scheduling) and detects and responds to cluster events. It comprises a collection of critical components that can run on a single master node or be replicated across multiple masters for high availability.

- API Server (

kube-apiserver): This is the central hub for all cluster communication and the front-end for the control plane. It exposes the Kubernetes API, processing REST requests, validating them, and updating the cluster's state inetcd. - etcd: A consistent and highly-available key-value store used as Kubernetes' backing store for all cluster data. It is the single source of truth, storing the desired and actual state of every object in the cluster.

- Scheduler (

kube-scheduler): This component watches for newly created Pods that have no assigned node and selects a node for them to run on. The scheduling decision is based on resource requirements, affinity/anti-affinity rules, taints and tolerations, and other constraints. - Controller Manager (

kube-controller-manager): This runs controller processes that regulate the cluster state. Logically, each controller is a separate process, but they are compiled into a single binary for simplicity. Examples include the Node Controller, Replication Controller, and Endpoint Controller.

This distributed control mechanism ensures that the cluster can maintain the application's desired state even if individual components fail.

The Kubernetes Worker Node Components

Worker nodes are the machines (VMs or bare metal) where application containers are executed. Each worker node is managed by the control plane and contains the necessary services to run Pods—the smallest and simplest unit in the Kubernetes object model that you create or deploy.

- Kubelet: An agent that runs on each node in the cluster. It ensures that containers described in PodSpecs are running and healthy. It communicates with the control plane and the container runtime.

- Kube-proxy: A network proxy running on each node that maintains network rules. These rules allow network communication to your Pods from network sessions inside or outside of your cluster, implementing the Kubernetes Service concept.

- Container Runtime: The software responsible for running containers. Kubernetes supports any runtime that implements the Container Runtime Interface (CRI), such as containerd or CRI-O. This component pulls container images from a registry, and starts and stops them.

This clean separation of concerns—management (Control Plane) vs. execution (Worker Nodes)—is the source of Kubernetes' power. It is an architecture designed from inception to orchestrate complex, distributed workloads.

Technical Feature Analysis and Comparison

Beyond high-level architecture, the practical differences between Docker and Kubernetes emerge in their core operational features. Docker, often used with Docker Compose, provides a solid foundation for single-host deployments. Kubernetes adds a layer of automated intelligence designed for distributed systems.

Let's perform a technical breakdown of how they handle scaling, networking, storage, and resilience.

To fully appreciate the orchestration layer Kubernetes provides, it is essential to first understand the container layer. This Docker container tutorial for beginners provides the foundational knowledge required.

Scaling Mechanisms: Manual vs. Automated

One of the most significant operational divides is the approach to scaling. Docker's approach is imperative and manual, while Kubernetes employs a declarative, automated model.

With Docker Compose, scaling a service is an explicit command. You directly instruct the Docker daemon to adjust the number of container instances. This is straightforward for predictable, manual adjustments on a single host.

For instance, to scale a web service to 5 instances using a docker-compose.yml file, you execute:

docker-compose up --scale web=5 -d

This command instructs the Docker Engine to ensure five containers for the web service are running. However, this is a point-in-time operation. If one container crashes or traffic surges, manual intervention is required to correct the state or scale further.

Kubernetes introduces the Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA), which automatically adjusts the number of Pods in a ReplicaSet, Deployment, or StatefulSet based on observed metrics like CPU utilization or custom metrics. You declare the desired state, and the Kubernetes control loop works to maintain it.

A basic HPA manifest is defined in YAML:

apiVersion: autoscaling/v2

kind: HorizontalPodAutoscaler

metadata:

name: my-app-hpa

spec:

scaleTargetRef:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

name: my-app

minReplicas: 2

maxReplicas: 10

metrics:

- type: Resource

resource:

name: cpu

target:

type: Utilization

averageUtilization: 60

This declarative approach enables true, hands-off autoscaling, a critical requirement for production systems with variable load.

Key Differentiator: Docker requires imperative, command-driven scaling. Kubernetes provides declarative, policy-driven autoscaling based on real-time application load, which is essential for resilient production systems.

Service Discovery and Networking

Container networking is complex, and the approaches of Docker and Kubernetes reflect their different design goals. Docker's networking is host-centric, while Kubernetes provides a flat, cluster-wide networking fabric.

By default, Docker uses bridge networks, creating a private L2 segment on the host machine. Containers on the same bridge network can resolve each other's IP addresses via container name using Docker's embedded DNS server. This is effective for applications running on a single server but does not natively extend across multiple hosts.

Kubernetes implements a more abstract and powerful networking model designed for clusters.

- Cluster-wide DNS: Every Service in Kubernetes gets a stable DNS A/AAAA record (

my-svc.my-namespace.svc.cluster-domain.example). This allows Pods to reliably communicate using a consistent name, regardless of the node they are scheduled on or if they are restarted. - Service Objects: A Kubernetes

Serviceis an abstraction that defines a logical set of Pods and a policy by which to access them. It provides a stable IP address (ClusterIP) and DNS name, and load balances traffic to the backend Pods. This decouples clients from the ephemeral nature of Pods.

This means you never directly track individual Pod IP addresses. You communicate with the stable Service endpoint, and Kubernetes handles the routing and load balancing.

Operational Feature Comparison

This table provides a technical breakdown of how each platform handles day-to-day operational tasks.

| Feature | Docker Approach | Kubernetes Approach | Key Differentiator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaling | Manual, imperative commands (docker-compose --scale). Requires human intervention to respond to load. |

Automated and declarative via the Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA). Scales based on metrics like CPU/memory. | Automation. Kubernetes scales without manual input, reacting to real-time conditions. |

| Networking | Host-centric bridge networks. Simple DNS for containers on the same host. Multi-host requires extra tooling. | Cluster-wide, flat network model. Built-in DNS and Service objects provide stable endpoints and load balancing. | Scope. Kubernetes provides a native, resilient networking fabric for distributed systems out of the box. |

| Storage | Host-coupled Volumes. Data is tied to a specific directory on a specific host machine. | Abstracted via PersistentVolumes (PV) and PersistentVolumeClaims (PVC). Storage is a cluster resource. | Portability. Kubernetes decouples storage from nodes, allowing stateful pods to move freely across the cluster. |

| Health Management | Basic container restart policies (restart: always). No automated health checks or workload replacement. |

Proactive self-healing. Liveness/readiness probes detect failures; controllers replace unhealthy Pods automatically. | Resilience. Kubernetes is designed to automatically detect and recover from failures, a core production need. |

This comparison makes it clear: Docker provides the essential tools for running containers on a single host, while Kubernetes builds an automated, resilient platform around those containers for distributed environments.

Storage Management Abstraction Levels

Stateful applications require persistent storage, and the two platforms offer different levels of abstraction.

Docker's solution is Volumes. A Docker Volume maps a directory on the host filesystem into a container. Docker manages this directory, and since it exists outside the container's writable layer, data persists even if the container is removed. This is effective but tightly couples the storage to a specific host.

Kubernetes introduces a two-part abstraction to decouple storage from specific nodes:

- PersistentVolume (PV): A piece of storage in the cluster that has been provisioned by an administrator. It is a cluster resource, just like a node is a cluster resource. PVs have a lifecycle independent of any individual Pod that uses the PV.

- PersistentVolumeClaim (PVC): A request for storage by a user. It is similar to a Pod. Pods consume node resources; PVCs consume PV resources.

A developer defines a PVC in their application manifest, requesting a specific size and access mode (e.g., ReadWriteOnce). Kubernetes dynamically provisions a matching PV (using a StorageClass) or binds the claim to an available pre-provisioned PV. This model allows stateful Pods to be scheduled on any node in the cluster while maintaining access to their data.

Self-Healing and Resilience

Finally, the most critical differentiator for production systems is self-healing.

Docker has no native mechanism for application-level health checking. If a container crashes, it can be restarted based on a configured policy (e.g., restart: always), but if the application inside the container deadlocks or becomes unresponsive, Docker has no way to detect this.

Self-healing is a core design principle of Kubernetes. The Controller Manager and Kubelet work together to constantly reconcile the cluster's current state with its desired state.

- Liveness Probes: Kubelet periodically checks if a container is still alive. If the probe fails, Kubelet kills the container, and its controller (e.g., ReplicaSet) creates a replacement.

- Readiness Probes: Kubelet uses this probe to know when a container is ready to start accepting traffic. Pods that fail readiness probes are removed from Service endpoints.

This automated failure detection and recovery is what elevates Kubernetes to a production-grade orchestration platform. It's not just about running containers; it's about ensuring the service they provide remains available.

Choosing the Right Tool for the Job

The decision between Docker and Kubernetes is not about which is "better," but which is appropriate for the task's scale and complexity. The choice represents a trade-off between operational simplicity and the raw power required for distributed systems.

Getting this decision right prevents over-engineering simple projects or, more critically, under-equipping complex applications destined for production. A solo developer building a prototype has vastly different requirements than an enterprise operating a distributed microservices architecture.

This diagram illustrates the core decision point.

The primary question is whether you require automated scaling, fault tolerance, and multi-node orchestration. If the answer is yes, the path leads directly to Kubernetes.

When Docker Standalone Is the Superior Choice

For many scenarios, the operational overhead of a Kubernetes cluster is not only unnecessary but counterproductive. This is where Docker, especially when combined with Docker Compose, excels through its simplicity and speed.

- Local Development Environments: Docker provides developers with consistent, isolated environments that mirror production. It is unparalleled for building and testing multi-container applications on a local machine without cluster management complexity.

- CI/CD Build Pipelines: Docker is the ideal tool for creating clean, ephemeral, and reproducible build environments within CI/CD pipelines. It packages the application into an immutable image, ready for subsequent testing and deployment stages.

- Single-Node Applications: For simple applications or services designed to run on a single host—such as internal tools, small web apps, or background job processors without high-availability requirements—Docker provides sufficient functionality.

The rule of thumb is: if the primary challenge is application packaging and consistent execution on a single host, use Docker. Introducing an orchestrator at this stage adds unnecessary layers of abstraction and complexity.

Scenarios That Demand Kubernetes

As an application's scale and complexity grow, the limitations of a single-host setup become apparent. Kubernetes was designed specifically to solve the operational challenges of managing containerized applications across a fleet of machines.

- Distributed Microservices Architectures: When an application is decomposed into numerous independent microservices, a system to manage their lifecycle, networking, configuration, and discovery is essential. Kubernetes provides the robust orchestration and service mesh integrations required for such architectures.

- Stateful Applications Requiring High Availability: For systems like databases or message queues that require persistent state and must remain available during node failures, Kubernetes is critical. Its self-healing capabilities, combined with StatefulSets and PersistentVolumes, ensure data integrity and service uptime.

- Multi-Cloud and Hybrid Deployments: Kubernetes provides a consistent API and operational model that abstracts the underlying infrastructure, whether on-premises or across multiple cloud providers. This prevents vendor lock-in and enables true workload portability.

Choosing the right infrastructure is also key. The decision goes beyond orchestration to the underlying compute, such as the trade-offs between cloud server vs. dedicated server models. For a broader view of the landscape, you can explore the best container orchestration tools.

The pragmatic approach is to start with Docker for development and simple deployments. When the application's requirements for scale, resilience, and operational automation exceed the capabilities of a single node, it is time to adopt the production-grade power of Kubernetes.

How Docker and Kubernetes Work Together

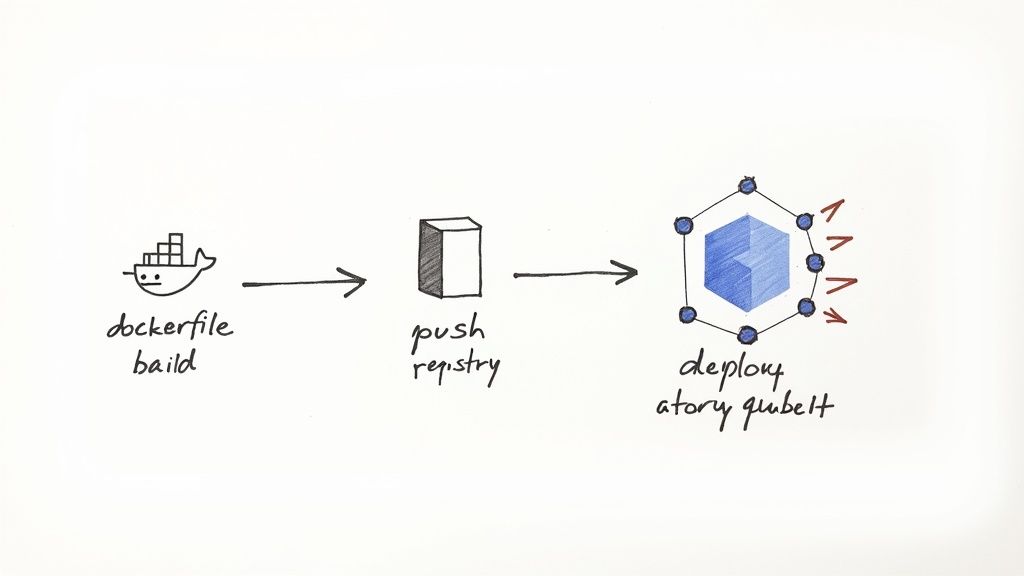

The idea of Docker and Kubernetes as competitors is a misconception. They form a symbiotic relationship, representing two essential stages in a modern cloud-native delivery pipeline.

Docker addresses the "build" phase: it packages an application and its dependencies into a standardized, portable OCI container image. Kubernetes, in turn, addresses the "run" phase: it takes those container images and automates their deployment, management, and scaling in a distributed environment.

This partnership forms the backbone of a typical DevOps workflow, enabling a seamless transition from a developer's machine to a production cluster.

This integrated workflow guarantees environmental consistency from local development through to production, finally solving the "it works on my machine" problem. Each tool has a clearly defined responsibility, handing off the artifact at the appropriate stage.

The Standard DevOps Workflow Explained

The process of moving code to a running application in Kubernetes follows a well-defined, automated path that leverages the strengths of both technologies. Docker creates the deployable artifact, and Kubernetes provides the production-grade runtime.

Here is a step-by-step technical breakdown of this collaboration.

Step 1: Write the Dockerfile

The workflow begins with the Dockerfile, a text file containing instructions to assemble a container image. It specifies the base image, source code location, dependencies, and the command to execute when the container starts.

A simple Dockerfile for a Node.js application:

# Use an official Node.js runtime as a parent image

FROM node:18-alpine

# Set the working directory in the container

WORKDIR /usr/src/app

# Copy package.json and package-lock.json to leverage build cache

COPY package*.json ./

# Install app dependencies

RUN npm install

# Bundle app source

COPY . .

# Expose the application port

EXPOSE 8080

# Define the command to run the application

CMD [ "node", "server.js" ]

This file is the declarative blueprint for the application's runtime environment.

Step 2: Build and Tag the Docker Image

A developer or a CI/CD server executes the docker build command. Docker reads the Dockerfile, executes each instruction, and produces a layered, immutable container image.

docker build -t my-username/my-cool-app:v1.0 .

This command creates an image named my-cool-app with the tag v1.0.

Step 3: Push the Image to a Container Registry

The built image is pushed to a central container registry, such as Docker Hub, Google Container Registry (GCR), or Amazon Elastic Container Registry (ECR). This makes the image accessible to the Kubernetes cluster.

docker push my-username/my-cool-app:v1.0

At this stage, Docker's primary role is complete. It has produced a portable, versioned artifact ready for deployment.

Deploying the Image with Kubernetes

Kubernetes now takes over to handle orchestration. Kubernetes does not build images; it consumes them. It uses declarative YAML manifests to define the desired state of the running application.

Step 4: Create a Kubernetes Deployment Manifest

A Deployment is a Kubernetes API object that manages a set of replicated Pods. The following YAML manifest instructs Kubernetes which container image to run and how many replicas to maintain.

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: my-cool-app-deployment

spec:

replicas: 3

selector:

matchLabels:

app: my-cool-app

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: my-cool-app

spec:

containers:

- name: my-app-container

image: my-username/my-cool-app:v1.0

ports:

- containerPort: 8080

The spec.template.spec.containers[0].image field points directly to the image pushed to the registry in the previous step.

Step 5: Apply the Manifest to the Cluster

Finally, the kubectl command-line tool is used to submit this manifest to the Kubernetes API server.

kubectl apply -f deployment.yaml

Kubernetes now takes control. Its controllers read the manifest, schedule Pods onto nodes, instruct the kubelets to pull the specified Docker image from the registry, and continuously work to ensure that three healthy replicas of the application are running.

This workflow perfectly illustrates the separation of concerns. Docker is the builder, responsible for packaging the application at build time. Kubernetes is the manager, responsible for orchestrating and managing that package at runtime.

Understanding the Kubernetes Ecosystem

Kubernetes achieved dominance not just through its technical merits, but through the powerful open-source ecosystem that developed around it. Docker provided the standard for containers; Kubernetes provided the standard for orchestrating them, largely due to its open governance and extensible design.

Housed within the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF), Kubernetes benefits from broad industry collaboration, ensuring it remains vendor-neutral. This fosters trust and prevents fragmentation, giving enterprises the confidence to build on a stable, long-lasting foundation.

The Power of Integrated Tooling

This open, collaborative model has fostered a rich ecosystem of specialized tools that integrate deeply with the Kubernetes API to solve specific operational problems. These tools elevate Kubernetes from a core orchestrator to a comprehensive application platform.

A few key examples that have become de facto standards:

- Prometheus for Monitoring: The standard for metrics-based monitoring and alerting in cloud-native environments, providing deep visibility into cluster and application performance.

- Helm for Package Management: A package manager for Kubernetes that simplifies the deployment and management of complex applications using versioned, reusable packages called Charts.

- Istio for Service Mesh: A powerful service mesh that provides traffic management, security (mTLS), and observability at the platform layer, without requiring changes to application code.

Kubernetes' true strength lies not just in its core functionality, but in its extensibility. Its API-centric design and CNCF stewardship have created a gravitational center, attracting the best tools and talent to build a cohesive, enterprise-grade platform.

Market Drivers and Explosive Growth

The enterprise shift to microservices architectures created a demand for a robust orchestration solution, and Kubernetes filled that need perfectly. Its ability to manage complex distributed systems while offering portability across hybrid and multi-cloud environments made it the clear choice for modern infrastructure.

Market data validates this trend. The Kubernetes market was valued at USD 1.8 billion in 2022 and is projected to reach USD 9.69 billion by 2031, growing at a CAGR of 23.4%. This reflects its central role in any scalable, cloud-native strategy. You can review the analysis in Mordor Intelligence's full report.

Whether deployed on a major cloud provider or on-premises, its management capabilities are indispensable—a topic explored in our guide to running Kubernetes on bare metal. This surrounding ecosystem provides long-term value and solidifies its position as the industry standard.

Frequently Asked Questions

When working with Docker and Kubernetes, several key technical questions consistently arise. Here are clear, practical answers to the most common queries.

Can You Use Kubernetes Without Docker?

Yes, absolutely. The belief that Kubernetes requires Docker is a common misconception rooted in its early history. Kubernetes is designed to be runtime-agnostic through the Container Runtime Interface (CRI), a plugin interface that enables kubelet to use a wide variety of container runtimes.

While Docker Engine was the initial runtime, direct integration via dockershim was deprecated in Kubernetes v1.20 and removed in v1.24. Today, Kubernetes works with any CRI-compliant runtime, such as containerd (the industry-standard core runtime component extracted from the Docker project) or CRI-O. This decoupling is a crucial architectural feature that ensures Kubernetes remains flexible and vendor-neutral.

Is Docker Swarm a Viable Kubernetes Alternative?

Docker Swarm is Docker's native orchestration engine. It offers a much simpler user experience and a gentler learning curve, as its concepts and CLI are tightly integrated with the Docker ecosystem. For smaller-scale applications or teams without dedicated platform engineers, it can be a viable choice.

However, for production-grade, large-scale deployments, Kubernetes operates in a different class. It offers far more powerful and extensible features for networking, storage, security, and observability.

For enterprise-level requirements, Kubernetes is the undisputed industry standard due to its declarative API, powerful auto-scaling, sophisticated networking model, vast ecosystem, and robust self-healing capabilities. Swarm is simpler, but its feature set and community support are significantly more limited.

When Should You Use Docker Compose Instead of Kubernetes?

The rule is straightforward: use Docker Compose for defining and running multi-container applications on a single host. It is the ideal tool for local development environments, automated testing in CI/CD pipelines, and deploying simple applications on a single server. Its strength lies in its simplicity for single-node contexts.

Use Kubernetes when you need to deploy, manage, and scale that application across a cluster of multiple machines. If your requirements include high availability, zero-downtime deployments, automatic load balancing, self-healing, and dynamic scaling, Kubernetes is the appropriate tool for the job.

Ready to harness the power of Kubernetes without the operational overhead? OpsMoon connects you with the top 0.7% of DevOps engineers to build, manage, and scale your cloud-native infrastructure. Start with a free work planning session to map your path to production excellence. Learn more at OpsMoon.