A Technical Guide to the Internal Developer Platform

Discover what an Internal Developer Platform (IDP) is and how it drives efficiency. Our guide covers core components, implementation, and ROI.

An internal developer platform (IDP) is a self-service layer built by a platform team to automate and standardize the software delivery lifecycle. Architecturally, it's a composition of tools, APIs, and workflows that provide developers with curated, self-service capabilities. Think of it as a centralized API for your infrastructure, enabling engineering teams to provision resources, deploy services, and manage operations without deep infrastructure expertise.

Unlocking Engineering Velocity

In modern software organizations, developers face a combinatorial explosion of tooling. To ship a feature, an engineer must interact with Kubernetes YAML, navigate cloud provider IAM policies, configure CI/CD jobs, and instrument observability. This cognitive load directly detracts from their primary function: designing and implementing business logic.

An IDP mitigates this by creating a "paved road"—a set of well-defined, automated pathways for common engineering tasks. Instead of each developer navigating a complex toolchain, the platform team provides a stable, supported infrastructure highway. This abstraction layer enables developers to move from local git commit to a production deployment rapidly, safely, and repeatably.

The goal is to abstract away the underlying infrastructure complexity. Developers interact with the IDP's higher-level abstractions (e.g., "deploy my service" or "provision a Postgres database") rather than directly manipulating low-level resources like Kubernetes Deployments, Services, and Ingresses.

The Core Problem an IDP Solves

At its core, an internal developer platform is designed to reduce developer cognitive load. When engineers are burdened with operational tasks, productivity plummets and innovation stalls. An IDP centralizes and automates these tasks, abstracting away the underlying complexity and freeing developers to focus on application code.

This shift delivers tangible engineering and business outcomes:

- Deployment Frequency: Standardized, automated CI/CD pipelines enable teams to increase deployment velocity and ship code with higher confidence.

- Security and Compliance: Security policies (e.g., static analysis scans, container vulnerability scanning) and governance rules are embedded directly into the platform's workflows. This ensures every deployment adheres to organizational standards by default.

- Developer Retention: High-performance engineering environments with low friction and high autonomy are a key factor in attracting and retaining top talent.

The real magic happens when developers no longer have to file a ticket for every little infrastructure request. A task that once meant days of waiting for an ops team can now be done in minutes through a simple self-service portal.

How an IDP Drives Business Value

Ultimately, an IDP isn't just a technical tool; it's a strategic investment in engineering efficiency. It streamlines workflows, enforces best practices through automation, and creates a scalable foundation for growth.

This is the central tenet of platform engineering, a discipline focused on building and operating internal platforms as products for developer customers. For a deeper dive, you can explore the relationship between platform engineering vs DevOps in our detailed guide. When executed correctly, an IDP becomes a powerful force multiplier, accelerating product delivery and business goal attainment.

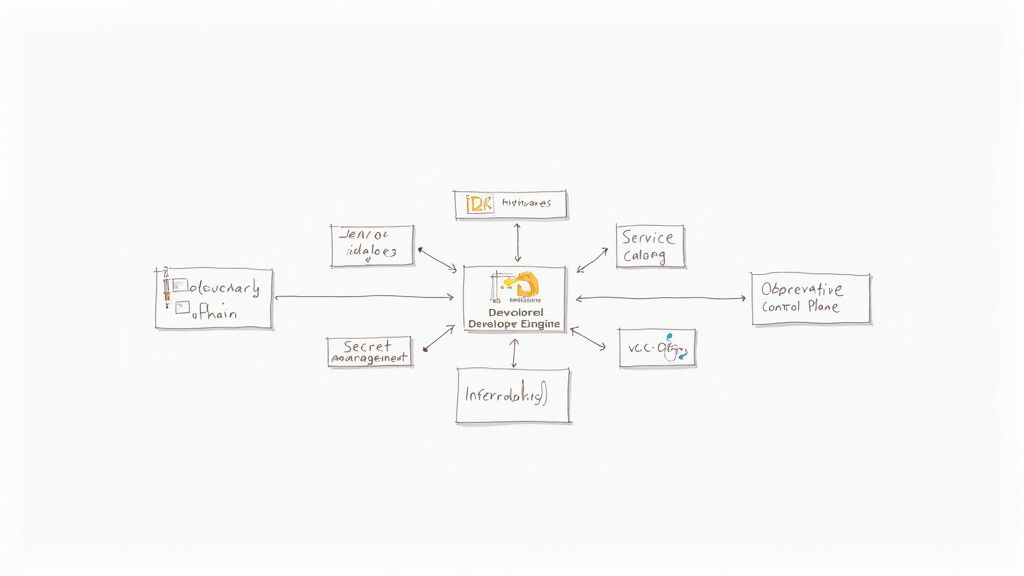

Exploring the Core Components of a Modern IDP

A robust internal developer platform is not a monolithic application but a composition of integrated components. It abstracts infrastructure complexity through a set of key building blocks that provide a seamless, self-service experience.

Architecturally, this can be modeled as a control plane and a user-facing interface. The orchestration engine acts as the control plane, interpreting developer intent and executing workflows across the underlying toolchain. The developer portal serves as the user interface, providing a single pane of glass for developers to interact with the platform's capabilities.

The Developer Portal and Service Catalog

The developer portal is the primary interaction point for engineering teams. It's the API/UI through which developers discover, provision, and manage software components without needing direct access to underlying infrastructure like Kubernetes or cloud consoles.

A critical feature of the portal is the service catalog. This is a curated repository of reusable software templates, infrastructure patterns, and data services. For example, a developer can use the catalog to scaffold a new microservice from a template that includes pre-configured Dockerfiles, CI/CD pipeline definitions (.gitlab-ci.yml), logging agents, and security manifests.

This approach yields significant technical benefits:

- Standardization: Enforces organizational best practices (e.g., logging formats, security context constraints) from the moment a service is created.

- Discoverability: Provides a centralized, searchable inventory of internal services, APIs, and their ownership, reducing redundant work.

- Accelerated Onboarding: New engineers can become productive faster by leveraging established, well-documented service templates.

Infrastructure as Code and Automation

The automation engine behind the portal is powered by Infrastructure as Code (IaC). An IDP leverages IaC frameworks like Terraform, Pulumi, or Crossplane to define and provision infrastructure declaratively, ensuring repeatability and consistency.

When a developer requests a new preview environment via the portal, the orchestration engine triggers the corresponding IaC module. This module then executes API calls to the cloud provider (e.g., AWS, GCP) to provision all necessary resources—VPCs, subnets, Kubernetes clusters, databases—ensuring each environment is an exact, version-controlled replica.

This is where the magic of an internal developer platform really shines. By turning infrastructure into code, the platform gets rid of manual setup mistakes and the classic "it works on my machine" headache, which are huge sources of friction in deployments.

This deep automation is what makes the "paved road" a reality. A cornerstone of any modern Internal Developer Platform is a robust and efficient continuous integration and continuous delivery (CI/CD) pipeline; therefore, it's essential to understand the latest CI/CD pipeline best practices. The IDP integrates with version control systems (e.g., Git), automatically triggering build, test, and deployment jobs in tools like GitLab CI, GitHub Actions, or Jenkins upon code commits.

Integrated Observability and Security

A mature IDP extends beyond CI/CD to encompass Day-2 operations. It embeds observability directly into the developer workflow, providing immediate feedback on application performance in production.

The platform automatically instruments services to export key telemetry data:

- Metrics: Time-series data on performance (e.g., CPU/memory utilization, request latency, error rates) collected via agents like Prometheus.

- Logs: Structured event records (e.g., JSON format) aggregated into a centralized logging system like Loki or Elasticsearch.

- Traces: End-to-end request lifecycle visibility across distributed services, enabled by standards like OpenTelemetry.

This data is surfaced within the developer portal, allowing engineers to troubleshoot issues without requiring elevated access to production environments or separate tools.

Security is similarly integrated as a core, automated function. An IDP shifts security left by embedding controls throughout the development lifecycle. This includes centralized secret management using tools like HashiCorp Vault, which injects secrets at runtime rather than storing them in code, and Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) to enforce least-privilege access to platform resources.

Measuring the ROI of Your Platform Initiative

To secure funding for an internal developer platform, "improved productivity" is insufficient. A data-driven business case is required, translating technical improvements into quantifiable metrics that resonate with business leadership: velocity, stability, and cost.

Measuring the Return on Investment (ROI) involves establishing baseline KPIs before implementation and tracking them post-rollout to demonstrate tangible impact.

Quantifying Development Velocity

An IDP's initial impact is most visible in development velocity metrics. These should be measured and tracked rigorously.

- Developer Onboarding Time: Measure the time from a new engineer's first day to their first successful production commit. An IDP with standardized templates and self-service environment provisioning can reduce this from weeks to hours.

- Lead Time for Changes: A key DORA metric, this measures the time from code commit to production deployment. By automating CI/CD and eliminating manual handoffs, an IDP can decrease this from days to minutes.

- Deployment Frequency: Track the number of deployments per team per day. An IDP facilitates smaller, more frequent releases by reducing the friction and risk of each deployment. An increase in this metric indicates improved agility.

Measuring Stability and Quality Improvements

An IDP enhances system reliability by standardizing configurations and embedding quality gates into automated workflows. This stability can be quantified to demonstrate the platform's value.

A huge benefit of an IDP is that it makes the "right way" the "easy way." When security scans, tests, and compliance checks are baked into automated workflows, you slash the human errors that cause most production incidents.

Key stability metrics to monitor:

- Change Failure Rate (CFR): Calculate the percentage of deployments that result in a production incident requiring a rollback or hotfix. The standardized environments and automated testing within an IDP can drive this metric down significantly. It's not uncommon to see CFR drop from 15% to under 5%.

- Mean Time to Recovery (MTTR): Measure the average time required to restore service after a production failure. An IDP provides developers with self-service tools for rollbacks and integrated observability for rapid root cause analysis, dramatically reducing MTTR.

These metrics provide direct evidence of how an IDP improves developer productivity by minimizing time spent on firefighting and reactive maintenance.

Calculating Hard Cost Savings

Velocity and stability translate directly into cost savings. An IDP introduces efficiency and governance that can significantly reduce operational expenditures, particularly cloud infrastructure costs.

A recent industry study showed that over 65% of enterprises now use an IDP to get a better handle on governance. These companies ship software up to 40% faster, cut down on context-switching by 35%, and can slash monthly cloud bills by 20–30% just by having centralized visibility and automated cleanup. You can find more of these platform engineering trends in recent industry analysis.

Focus on tracking these financial wins:

- Cloud Resource Optimization: Analyze cloud spend on non-production environments. An IDP can enforce automated teardown of ephemeral development and staging environments, eliminating idle "zombie" infrastructure.

- Elimination of Shadow IT: Sum the costs of disparate, unmanaged tools across teams. An IDP centralizes the toolchain, eliminating redundant software licenses and support contracts.

- Developer Time Reallocation: Quantify the engineering hours previously spent on manual operational tasks (e.g., environment setup, pipeline configuration). Reclaiming even a few hours per developer per week yields a substantial financial return.

Making the Critical Build Versus Buy Decision

The decision to build a custom internal developer platform versus buying a commercial solution is a critical strategic inflection point. This choice impacts engineering culture, budget allocation, and product velocity for years.

The fundamental question is one of core competency: is your business to build developer tools or to ship your own product?

The Realities of Building In-House

The allure of a bespoke IDP is strong, promising perfect alignment with existing workflows and complete control. However, this path requires a significant, ongoing investment. You are not funding a project; you are launching a new internal product line and committing to staffing a dedicated platform team in perpetuity.

Building an IDP means establishing a complex software product organization within your company, treating your developers as its customers. This requires a dedicated team of engineers to not only build the initial version but to continuously maintain, secure, patch, and evolve it.

The initial build often takes 12 months or more to reach a minimum viable product. The subsequent operational burden is substantial.

- Never-Ending Maintenance: The underlying open-source components require constant security patching and upgrades. A significant portion of the platform team's time will be dedicated to this maintenance treadmill.

- Constant Feature Development: Developer requirements evolve, demanding new integrations, improved workflows, and support for new technologies. The platform team must manage a perpetual development backlog.

- Security and Compliance Nightmares: A custom-built platform introduces a unique attack surface. The internal team is 100% responsible for its security posture, including audits and compliance with standards like SOC 2 or GDPR.

Without this long-term commitment, homegrown platforms inevitably stagnate, becoming sources of technical debt and friction. If you're seriously considering this route, talking to an experienced DevOps consulting firm can provide a crucial reality check on the true costs and resources involved.

Evaluating Commercial IDP Solutions

The "buy" option offers a compelling alternative, especially for organizations prioritizing speed and efficiency. Commercial IDPs from vendors like Port, Backstage, and Humanitec provide enterprise-grade features and security out-of-the-box.

This approach shifts the platform team's focus from building foundational components to configuring and integrating a powerful tool. The time-to-value is dramatically reduced; teams can be operational on a mature platform in weeks, not years.

However, purchasing a solution involves trade-offs, including licensing costs, potential vendor lock-in, and limitations on deep customization. If your workflows are highly idiosyncratic, an off-the-shelf product may prove too rigid.

Market trends indicate a clear preference for the "buy" model, particularly among small and mid-sized businesses. Research shows that cloud-based IDPs now command over 85% of the market, signaling a strong trend toward leveraging commercial solutions to gain agility without the high upfront investment. You can learn more about the internal developer platform market to dig into these trends.

The build vs. buy decision is a classic engineering leadership dilemma. The following table provides a breakdown of key decision factors.

Build vs Buy Internal Developer Platform Comparison

| Factor | Build (In-House) | Buy (Commercial Solution) |

|---|---|---|

| Time to Value | Very slow (12-18+ months for an MVP). Value is delayed significantly. | Very fast (weeks to a few months). Immediate access to mature features. |

| Initial Cost | Extremely high. Requires hiring a dedicated platform team (engineers, PMs). | Lower upfront cost. Typically a subscription or licensing fee. |

| Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) | Perpetually high. Includes salaries, infrastructure, and ongoing maintenance. | Predictable. Based on subscription tiers, though costs can scale with usage. |

| Customization & Flexibility | Unlimited. The platform can be perfectly tailored to unique internal workflows. | Limited to vendor's capabilities. Configuration is possible, but deep changes are not. |

| Maintenance & Upgrades | 100% internal responsibility. Team must handle all bug fixes, security patches, and updates. | Handled by the vendor. Team is freed from maintenance burdens. |

| Features & Innovation | Dependent on the internal team's bandwidth and roadmap. Often slow to evolve. | Benefits from the vendor's R&D. Gains new features and integrations regularly. |

| Security & Compliance | Entirely on your team. Requires dedicated security expertise and auditing. | Handled by the vendor, who typically provides SOC 2, ISO, etc., compliance. |

| Vendor Lock-in | No vendor lock-in, but you're "locked in" to your own custom technology and team. | A real risk. Migrating away can be complex and costly. |

| Team Focus | Shifts focus from core product development to internal tool development. | Allows engineering teams to stay focused on delivering customer-facing products. |

For most companies, whose core business is not building developer tools, the strategic advantage lies in accelerating time-to-market. This often makes a commercial solution the more prudent long-term investment.

An Actionable Roadmap for IDP Implementation

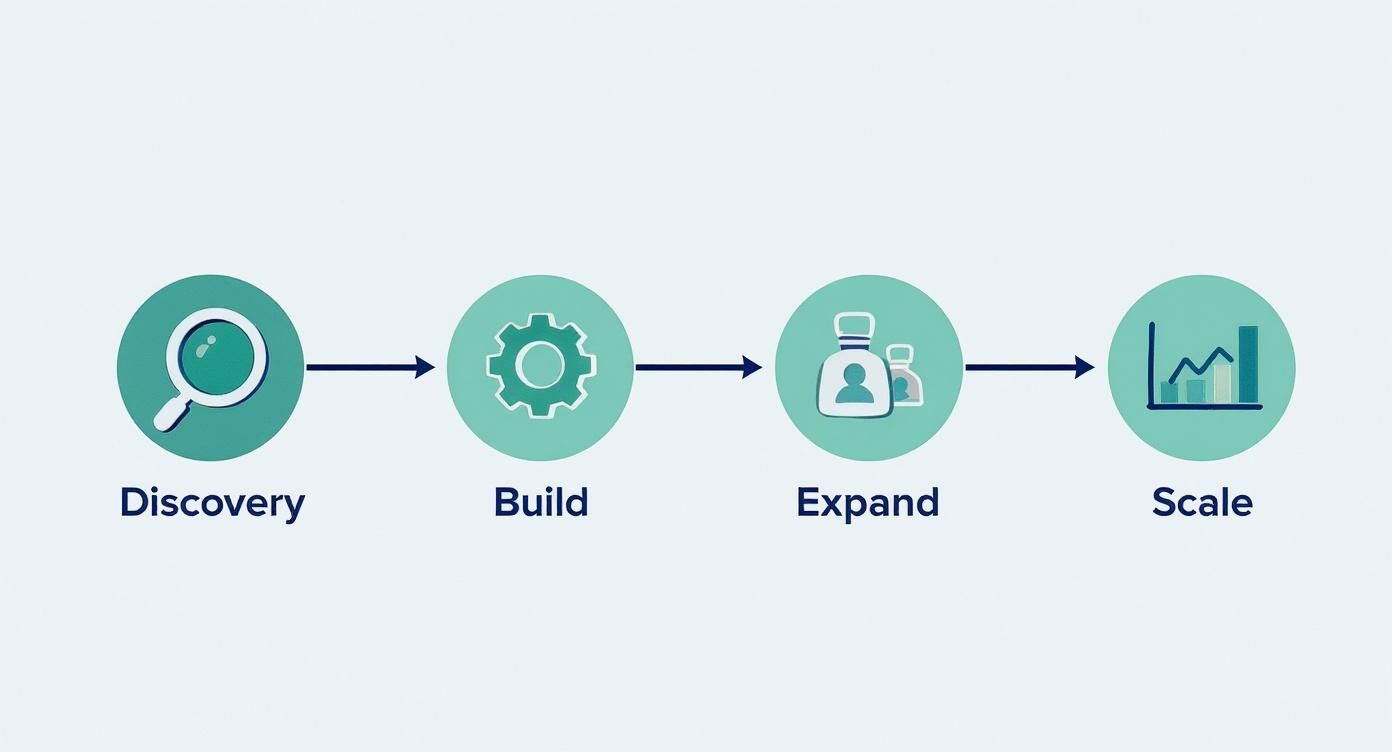

Implementing an internal developer platform is not a monolithic project but a product development journey. A phased, iterative approach is essential, treating the platform as a product and developers as its customers. Avoid a "big bang" release; success comes from delivering incremental value, gathering feedback, and iterating.

The diagram below outlines a four-phase implementation journey, from initial discovery to scaled governance.

This is a continuous improvement loop, starting with a targeted solution and expanding based on empirical feedback and measured results.

Phase 1: Discovery and MVP Definition

Before writing any code, conduct thorough user research. Interview developers, team leads, and operations engineers to identify the most significant points of friction in the current software delivery lifecycle.

Common pain points include slow environment provisioning, inconsistent CI/CD configurations, or the cognitive overhead of managing cloud resources. The objective is to identify the single most acute pain point that an IDP can solve immediately.

Based on this, define the scope for a Minimum Viable Platform (MVP). The goal is not feature completeness but the creation of a single, well-supported "golden path" for a specific, high-impact use case.

A classic mistake is trying to boil the ocean by supporting every language and framework from day one. A winning MVP might only support one type of service (like a stateless Go microservice), but it will do it exceptionally well, automating everything from

git committo a running staging environment.

Phase 2: Foundational Build and Pilot Program

With a well-defined MVP scope, the platform team begins building the foundational components. This involves integrating existing, battle-tested tools to create a seamless workflow, not building from scratch.

An initial technology stack might include:

- Infrastructure as Code: A set of version-controlled Terraform or Pulumi modules for standardized environment provisioning.

- CI/CD Integration: Webhooks connecting a source control manager (e.g., GitHub) to a CI/CD tool (e.g., GitLab CI) to automate builds and tests.

- A Simple Developer Interface: This could be a CLI tool or a basic web portal that triggers the underlying automation workflows.

As you lay the groundwork, pulling in expertise on topics like AWS migration best practices can be a huge help, especially if you're refining your cloud setup. The objective is to create a functional, end-to-end workflow.

Select a single, receptive engineering team to act as the pilot user. Provide them with dedicated support and closely observe their interaction with the platform. Their feedback is invaluable for identifying workflow gaps and areas for improvement.

Phase 3: Iteration and Expansion

The pilot program serves as a feedback loop. Use the insights gathered to drive a cycle of rapid iteration, refining the existing golden path and adding new capabilities based on demonstrated user needs.

Prioritize the backlog based on user feedback. If the pilot team struggled with log aggregation, prioritize observability features. If they requested a better secret management workflow, integrate a tool like HashiCorp Vault.

Once the initial golden path is stable and validated, begin expanding the platform's scope in two dimensions:

- Onboarding More Teams: Systematically roll out the existing functionality to other teams with similar use cases.

- Adding New Golden Paths: Begin developing support for a second service type, such as a Python data processing application or a Node.js frontend.

Phase 4: Scale and Governance

As adoption grows, the focus shifts from feature development to long-term sustainability and governance. The platform must be managed as a critical internal product.

This requires adopting a formal platform-as-a-product operating model. The platform team needs clear ownership, a public roadmap, defined service-level objectives (SLOs), and a formal support structure.

Key activities in this phase include:

- Measuring Success: Continuously track KPIs (e.g., deployment frequency, lead time for changes) to demonstrate the platform's ongoing business value.

- Establishing Governance: Define clear, lightweight policies for contributing new components to the service catalog and extending platform functionality.

- Fostering a Community: Cultivate a culture of shared ownership through comprehensive documentation, regular office hours, and internal user groups or Slack channels.

This phased approach transforms a daunting technical initiative into a manageable, value-driven process that builds developer trust and delivers measurable business outcomes.

Common IDP Implementation Pitfalls to Avoid

Implementing an internal developer platform is a high-stakes endeavor. Success often hinges less on technical brilliance and more on avoiding common, people-centric pitfalls that can derail the initiative.

A well-executed IDP acts as a force multiplier for engineering. A poorly executed one becomes a new, expensive bottleneck.

One of the most common failure modes is building the platform in an organizational vacuum. When a platform team operates in isolation, making assumptions about developer workflows, they build a product for a user they don't understand. This "if you build it, they will come" approach is a recipe for zero adoption.

If your developers see the new platform as just another roadblock to work around—instead of a tool that actually solves their problems—you've already lost. Your developers are your customers. Start treating them like it from day one.

This requires a fundamental mindset shift. The platform team must engage in continuous user research, interviewing developers, mapping value streams, and using that qualitative data to drive the product roadmap.

Overambitious Scope and the MVP Trap

Another frequent cause of failure is attempting to build a comprehensive, feature-complete platform from the outset. Teams that aim for 100% feature parity on day one, trying to support every existing technology stack and deployment pattern, are setting themselves up for failure.

This approach leads to protracted development cycles, often 12 to 18 months, to produce an initial version. By the time it launches, developer needs have evolved, and the initial momentum is lost.

A more effective strategy is to deliver a lean Minimum Viable Platform (MVP). Identify the single greatest point of friction—for example, the manual process of provisioning a development environment for a specific microservice archetype—and deliver a robust solution for that specific problem. This approach delivers tangible value to developers quickly, builds trust, and creates momentum for iterative expansion.

Underestimating the Human Element

Technical challenges are only part of the equation; organizational and cultural factors are equally critical. A common mistake is failing to establish a dedicated, empowered platform team with clear ownership of the IDP. When platform development is treated as a part-time side project, it is destined to fail.

Without clear ownership, the "platform" degenerates into a collection of unmaintained scripts and brittle automation. A successful platform team operates as a product team, with a product manager, dedicated engineers, and a long-term strategic vision.

Conversely, creating an overly prescriptive platform that removes all developer autonomy is also a recipe for failure. While standardization is a key benefit, an IDP that feels like a rigid cage will be met with resistance. Developers will inevitably create workarounds, leading to the exact shadow IT the platform was intended to eliminate.

The most effective platforms balance standardization with flexibility. They provide well-supported "golden paths" for common use cases while allowing for managed "escape hatches" when teams have legitimate needs to deviate from the standard path.

A Few Common Questions About IDPs

As organizations explore internal developer platforms, several key technical questions consistently arise. Clarifying these points is essential for engineering leaders and their teams.

What's the Difference Between an IDP and a Developer Portal?

This distinction is critical.

The internal developer platform (IDP) is the backend engine. It is the composition of APIs, controllers, and automation workflows that orchestrate the entire software delivery lifecycle—provisioning infrastructure via IaC, executing CI/CD pipelines, and managing deployments.

The developer portal is the frontend user interface. It is the single pane of glass (CLI or GUI) through which developers interact with the IDP's engine. It provides abstractions that allow developers to leverage the platform's power without needing to understand the underlying implementation details.

A portal without a platform is a static interface with no dynamic capabilities. A platform without a portal is a powerful engine with no user-friendly controls. Both are required for a successful implementation.

Can We Just Use Backstage as Our IDP?

No. Backstage is a powerful open-source framework for building a developer portal and service catalog. It provides an excellent user experience for service discovery, documentation, and project scaffolding.

However, Backstage is not an IDP by itself. It is a frontend framework and does not include the backend orchestration engine. You must integrate Backstage with an underlying platform that can execute the workflows it triggers—managing CI/CD, provisioning infrastructure, and deploying code.

Think of Backstage as the "control panel" of your platform; you still need to build or buy the "engine" that does the actual work.

Is GitOps Required to Build an IDP?

While not strictly mandatory, GitOps is the de facto modern standard for implementing the automation layer of an IDP. Using a Git repository as the declarative single source of truth for application and infrastructure state offers compelling advantages that are difficult to achieve otherwise.

- Auditability: Every change to the system's desired state is a version-controlled, auditable Git commit.

- Consistency: The GitOps controller continuously reconciles the live system state with the declared state in Git, preventing configuration drift.

- Reliability: Rollbacks are as simple as reverting a Git commit, providing a fast, reliable mechanism for disaster recovery.

Attempting to build an IDP without a GitOps model typically results in a collection of imperative, brittle automation scripts that are difficult to maintain and audit at scale.

Ready to stop building the factory and start shipping your product? At OpsMoon, we connect you with the top 0.7% of DevOps experts who can help you design, implement, and manage a high-impact platform engineering strategy. Schedule a free work planning session today to build your roadmap and accelerate your software delivery.